Club root is a devastating soil-borne disease of oilseed rape that may be on the rise in UK crops. CPM reports.

We’ve never had noticeable club root before on the farm but it must have already been there.

By Lucy de la Pasture

Plasmodiophora brassicae or club root – it’s a disease southern arable growers have seen in text books and one that strikes fear in the hearts of veggie growers, but for the vast majority it’s not a disease they’d be looking out for.

That may be all about to change after problems with club root infection appeared in oilseed rape at sites all over the country last winter, in situations where it had never been identified before and in virgin OSR ground.

So what’s going on? ADAS crop pathologist, Julie Smith, isn’t entirely surprised by the sudden appearance of club

The aerial symptoms of club root are thrifty looking plants, with stunting if infection is severe.

root last winter.

“We know club root needs wet soils to infect root hairs and an optimum daily mean temperature of 18-25°C, though when temperatures dip below a daily average of 16°C, the likelihood of infection is reduced,” she explains.

Taking weather data from 2014 in Herefordshire, there was a two-three week period where conditions would have been conducive for club root infection, which Julie Smith would consider a ‘normal’ season.

But in 2015, because it was so warm and wet around sowing, there was a huge window for infection, which extended the ‘normal’ risk period by an additional two to three weeks and gave club root a real opportunity to get going.

AHDB-funded research

“In collaboration with SRUC, we conducted a field survey as part of a previous AHDB-funded club root project (RD-2007-3373, 2007-11) and found a much higher percentage of club root infection in land than expected.

“Survey work showed the disease was present in all areas of the UK where OSR was grown and 52% of the surveyed sites tested positive for club root inoculum in the soil. These positive test results were often at sub-clinical levels in the crop,” she comments.

One of the problems with club root is that infection needs to be quite severe before there are obvious above-ground disease symptoms, says Julie Smith. “In order to find club root in the early stages, agronomists need to pull plants and look at the roots, though this is complicated by the fact that the disease is also notoriously patchy in occurrence.”

Published research shows that for every 10% of plants infected, yield is reduced by 0.3t/ha, so losses in affected crops can be over 50% of potential yield in the most severely infected crops. But complete plant loss is possible early season, with surviving plants suffering from the root galls caused by the disease, she reckons.

“I’ve seen yield penalties of more than more than 2t/ha in crops that have survived infection. The worrying fact about club root is that the resting spores are very robust and can last up to 20 years. The half-life of club root is approximately 4.5 years, which means levels of inoculum decline very slowly in the soil,” she says.

Exudates from host plant roots, which include common weeds such as charlock and shepherds purse, stimulate resting spores to germinate, so inoculum can continue to build even in the absence of an OSR crop. All in all, once soil is infected it’s a disease that’s very difficult to get rid of.

Club root in Northants

A Northants grower, James Mills, is facing this problem after club root was diagnosed in his OSR last autumn.

“The OSR crop was drilled 20-27 Aug and got away well. Then thinner areas began to appear in one field in an area 20-30m² and on closer inspection, you could see galls just above the soil surface,” he says.

“We’ve never had noticeable club root before on the farm but it must have already been there.”

According to his agronomist, Frontier’s Jon Yeoman, the rotation on the farm has always been sensible (1:3) and it’s not land he’d describe as sour, with liming taking place fairly routinely after the OSR crop.

The soil type is sandier than a lot of Northants soil and the club root interestingly seemed to be worst on the more alkaline, lighter soil, he says.

“The club root symptoms showed up very early and the severity of clinical

symptoms was unusual because of the open, mild autumn. The disease seemed to leapfrog its traditional pattern of development, with symptoms being evident this side of Christmas,” he comments.

The aerial symptoms of club root are thrifty looking plants, with stunting if infection is severe. If conditions are dry then the symptoms are exacerbated, with plants looking sick, wilted and stunted.

“The field where infection was first noticed had patches which grew bigger and bigger. By mid-Oct the crop looked so bad that we made the decision to apply glyphosate and put into beans in the spring,” says Jon Yeoman.

“Looking around the rest of the farm we’re now finding small patches of club root all over, though some of the big plants have recovered and are now looking fine,” he adds.

Secondary infection can be a problem in the spring and summer, says Julie Smith. “It’s something we’re seeing a lot of this year – infection that suddenly seems to get considerably worse as temperatures warm up.”

Resistant varieties

So for James Mills, what’s the best way forward? This autumn the first line of resistance will be using resistant cultivars, says Jon Yeoman, with new a new hybrid variety, Archimedes, looking interesting.

Julie Smith agrees that planting a resistant cultivar is a good start, though stresses that genetic resistance to club root can’t be exclusively relied upon.

“Resistance in current commercial cultivars is based on the Mendel gene and because it’s a single gene, the resistance is breaking down in some parts of the country.

“The trouble is that the Mendel gene resistance doesn’t protect against every pathotype of club root and some pathotypes are able to overcome the resistance,”

she explains, adding that a new AHDB-funded project is mapping to evaluate more precisely where these resistance breaking strains occur.

“We still don’t understand how far and how quickly patches of club root infection can spread in the field. The relationship between the inoculum density in the field and the severity of symptoms is also not yet fully understood. This new project will also attempt to find the answers to these questions,” she says.

Avoiding very early sowing of OSR is another way of reducing the likelihood of infection from club root occurring, advises Julie Smith. “When temperatures cool down, there’s a much better chance of avoiding the infection window for club root altogether,” she says.

Another strategy is to minimise soil movement to reduce the spread of inoculum within fields. This is something James Mills is keen to adopt. “We’ve traditionally always ploughed but are now going to move to a min-till system using a Great Plains Simba DTX,” he says.

Keeping soil pH in the range 7.0-7.3 is ideal to suppress club root development, says Julie Smith, though this may not be possible if there are potatoes in the rotation. “In our field trials we saw a reduction of clubroot from 70% to 30% when pH was increased from 6.5 to 7.3.

“Available calcium also has an impact and there are products available that have a rapid calcium burst, which appears to be more effective the straight agricultural lime,” she says.

“Supplying adequate levels of boron also helps make the crop more resilient.”

Other factors to consider are improving field drainage and extending the rotation to one brassica crop in five, she adds.

Overcoming the root gall

So how does club root affect yield and is there a way around it? David Marks, leading nutritional scientist, believes he may have the answer.

“The characteristic symptom of root galling or ‘clubbing’, leads to daytime wilting and nutrient deficiency due to reduced ability of the roots to transport food and

water to the growing plant. It’s this shortfall in nutrients and water transport that reduces yield,” he explains.

“The galls are undifferentiated cell masses (tumours), which give the pathogen a home to breed in and nutrients to feed on. The pathogen causes the plant to up-regulate auxin hormones and over-stimulate cell division.

“The effect on the plant is similar to a blocked pipe – it slows the flow of water and nutrients from the roots to the shoots by disrupting the vascular system. There’s also the added problem of tissue collapse, bringing in secondary infections,” he explains.

His research at Levity CropScience shows that supporting plants nutritionally can allow infected plants to maintain vascular structure, and guard against tissue collapse.

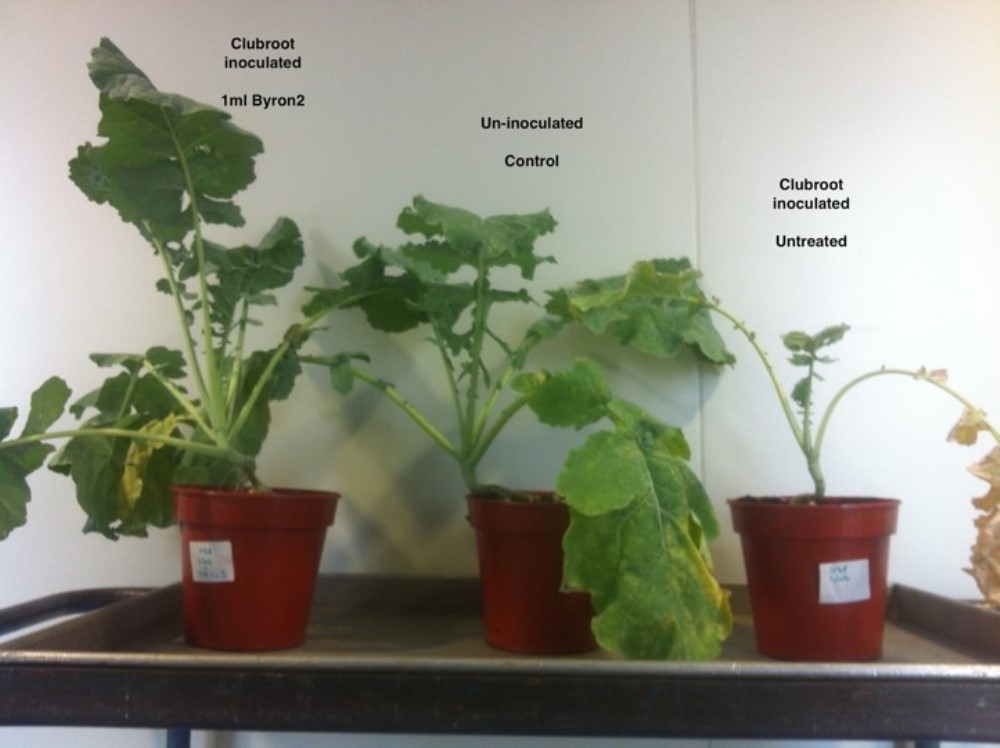

Inoculated canola in 2015 Canadian trials treated with Byron (left) compared with untreated (right) and control, un-inoculated plant (centre).

“The approach has produced excellent results in the lab, where we’ve been able to produce normal top growth and reduced galling despite infection. In studies at our Lancaster University facility, you can see how root growth was maintained on club root-inoculated OSR, grown using 1ml of nutritional supplement, Byron.

“The better root function led to better top growth, with treated plants showing no difference in growth to un-inoculated plants, while untreated plants showed severe growth retardation,” he says.

The promising work in the lab has been followed up with field trials in Canada, where club root symptoms were dramatically reduced. The product is now in field trials in the UK on cabbage and cauliflower, and due to be launched next season.

“The advantages of this approach are that the plant can grow despite club root infection using only a few litres of product per ha,” believes David Marks.

“This is a significant advantage over liming, which requires several tonnes of product and can negatively affect quality of potato crops the following season.”

However, Richard Cogman of British Sugar points out that ADAS trials have shown Limex is effective at reducing the effect of club root.

“Growers with a field history or susceptible varieties should min till or incorporate 5.0-7.5t/ha LimeX70,” he advises.

“This will reduce the pressure if a tolerant variety is grown and most importantly, it will reduce future inoculum.”