Spring wheat is generally considered a poor entry for oilseed rape, but one Cambs family business, determined to address problems with blackgrass and cabbage stem flea beetle, has made it work. CPM visits to find out how.

You need a variety which will get up quick and get going in the late slot.

By Tom Allen-Stevens

As the last of the seed pours into the hopper, the freshening breeze picks up the bag and turns it into a windsock which thrashes helplessly on the loader fork, as if signalling a change of weather.

Rain is indeed forecast, and Will Gee is keen to push on and establish what he can of the KWS Cochise spring wheat into the Grade 2 Fenland silts at Thorney, east of Peterborough, Cambs. The crop is being drilled a good month earlier than last year, and it’s part of a rotation that’s both addressing the farm’s blackgrass problem and allowing the oilseed rape crop to steer a path away from cabbage stem flea beetle damage.

The spring cultivations leave a good friable tilth for the autumn OSR crop.

“The spring wheat is grown for seed, which locks in a premium. But being later harvested, that pushes back the drilling date for the following OSR crop,” says Will. “What we’re finding, though, is that it makes quite a good entry for the OSR, which is yielding well, providing we use a variety that gets away well in the late slot. Or at least, we seem to be getting away with it at the moment.”

Will farms 650ha of arable crops with his brother Tom and father Edward. Joining the OSR, winter and spring wheat in the rotation are mustard, grown for Colmans, sugar beet and peas. While most of the wheats are grown for seed, the strategy with the OSR is to pick the right variety for the situation.

“When you find a variety you know you can work with, you stick with it, otherwise you don’t get a feel for how it performs,” he says. Previous varieties included growers’ favourites DK Cabernet, Castille and PR46W21. But currently the entire 97ha has been cropped with Campus.

The switch into the variety started in autumn 2017. Some land had been brought into the business with a relatively high blackgrass burden. “We took the decision not to grow winter wheat in some areas and go for spring wheat instead – it’s a crop we’ve grown on and off for years. We have a good relationship with Daltons, for whom we grow seed, and this is the second year we’ll be growing KWS Cochise.”

It’s proven a successful choice, with a yield last year of 6.7t/ha, despite the late spring and summer drought. The land is usually ploughed and pressed for spring wheat, with a spring tine or power harrow making the seedbed in front of the Väderstad Rapid drill.

“The spring cultivations ensure a seedbed free of blackgrass and also leave a good friable tilth for the autumn crop. There’s also less straw residue, so we drill the OSR straight into the stubble.”

That’s just as well, as the crop isn’t ready to harvest until late Aug to the beginning of Sept, pushing back the window for OSR establishment. “We get atrocious problems with CSFB here. To avoid the worst of the damage, you have to drill either early or late. Following spring wheat, clearly late is the only option, which means you need a variety which will get up quick and get going in the late slot,” he reasons.

Hybrids are the usual go-to option for late-sown vigour, but Will isn’t so sure. “We’ve grown both hybrids and open-pollinated varieties here, and I don’t really have a favourite. It’s simply a matter of picking the right variety for the situation. Daltons suggested Campus – it’s no longer one of the highest yielders available, but that’s not why we’re growing it.”

It was drilled at a fairly high seed rate – 5kg/ha – which usually works out at around 100 seeds/m². “You need the plant numbers when you’re drilling later,” he says.

But they didn’t get off scot-free from the CSFB. Three pyrethroid applications were needed to pull the crop through this autumn, while only one was required in autumn 2017.

“Last season we were lucky with the weather – we drilled and three days later it rained. This year it didn’t go quite as well, but the crop looks just as good now, and I don’t see any reason why it shouldn’t perform as well.”

The seed had a standard dressing with the addition of Radiate, adding some key micronutrients. Diammonium phosphate (DAP) was applied to the seedbed. “There was no need for a pre-emergence herbicide. We just applied Falcon (propaquizafop) for volunteers then followed up with Kerb (propyzamide) for the blackgrass once the soil conditions were right.”

The crop received a fungicide treatment in the autumn for phoma and a second treatment for light leaf spot. “Coming into the spring there was very little disease. We applied Proline (prothioconazole) at flowering to keep a check on sclerotinia,” says Will.

Last year’s late spring delayed the first nitrogen dressing, made as Sulphan to bring in the sulphur. This was followed up with the rest of the N applied as Extran just before flowering. Boron was also applied as a foliar treatment at the green-yellow bud stage.

“Once the crop got going there was plenty of growth, and we did apply a growth regulator. The aim was to treat with Caryx (mepiquat chloride+ metconazole) at stem extension, but in the end, it didn’t go on until green-yellow bud stage.

“But the treatment evened out the crop beautifully – there was no variation when it came to flowering and we had a canopy like a billiard table all the way through until harvest.”

No desiccant was needed for the 2018 harvest, although glyphosate is usually applied. The result was a yield of 4.9t/ha. “That’s pretty good for us. There’s a view that you can’t put OSR after spring wheat, but we’ve shown that if you give the crop every chance to succeed, you can still get a good result from late sowing.

“With the pressure from CSFB, you need a good reason to keep OSR in the rotation, and I think the result we’ve had provides that,” concludes Will.

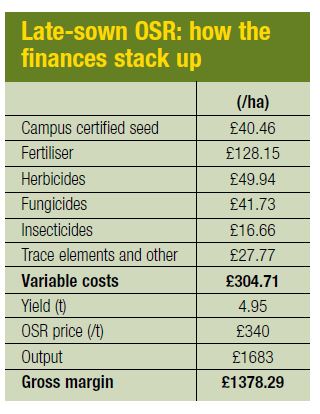

Late-sown OSR: how the finances stack up

Farm facts

Edward Gee and Sons, Thorney, nr Peterborough, Cambs

- Cropped area: 650ha

- Soil type: Predominantly mix of Grade 2 silts and heavier clay loam (Fen skirt)

- Staff: 2 full time

- Cropping: Winter wheat, spring wheat, winter oilseed rape, mustard, sugar beet, peas

- Mainline tractors: John Deere 7280R, 6930, 7530, plus one on hire at harvest

- Combine: New Holland CR9080 with 9m header

- Sprayer: Househam AR3500 with 24m boom

- Drill: 6m Väderstad Rapid

- Loader: JCB Loadall 536.60

- Fertiliser spreader: Sulky X40 with 3000kg hopper

- Cultivation: 5.5m Vaderstad Carrier; 2x 6f Dowdeswell ploughs; 4m Kuhn power harrow; 4m Maschio power harrow; 12.3m Cousins rolls

Partnership approach shares risk on establishment costs

KWS has introduced a new way to buy oilseed rape seed that reduces the up-front risk to growers.

Under the company’s Oilseed Establishment Partnership (OEP), those who buy the breeder’s new variety Blazen will pay a reduced royalty at the time the seed is purchased. The balance is then only paid if the crop is successfully established.

“We believe this sort of arrangement is unique,” says Julie Goult of KWS. “It’s an opportunity for growers to benefit from the genetics of a new, short and stiff conventional variety with a high yield, good disease resistance and strong tolerance of verticillium stem stripe, but they won’t suffer the full cost if the crop fails due to cabbage stem flea beetle or drought, for example.”

The idea is that the partnership shares the financial risk of a failed establishment between grower, merchant and KWS. The grower buys the seed from the merchant in the normal way at a reduced cost. There’s then an establishment levy in Nov, which won’t be payable if the crop has failed.

“It works in a similar way to the Royalty Area Collection which is widely used for niche crops, but until recently has not been offered for a broad-acre crop such as OSR,” notes Julie.

“It gives the grower all the assurances of certified seed and benefits of new genetics at a similar up-front cost to farm-saved seed (FSS).”

The aim is to encourage growers, who may have moved away from certified seed as a result of uncertainty over establishment, to reconsider the benefits it has over FSS. These include guaranteed genetics, independent purity and germination assessments, and erucic acid content assurance, she points out.

Typically the price for a 4ha seed pack will be £115-125. This will then be followed with an establishment fee of £28/ha. The scheme is managed by the Breeders’ Intellectual Property Office (BIPO), entirely outside the BSPB royalty collection scheme.

“There’s an on-line sign up, and BIPO will coordinate any auditing required. We won’t initially be making specific requirements on establishment practice, but we will invite growers and merchants to join an online forum that will include crop updates and crop-performance reports.

“I hope it will evolve into a true partnership and the information shared will help growers achieve a more certain establishment and enhanced returns from a crop that remains the most profitable autumn-sown break,” concludes Julie.

There are around 10,000 packs of Blazen available for establishment in autumn 2019. The variety is an AHDB Recommended List candidate for harvest 2019, with a gross output of 104% of controls, stem stiffness score of 8 and height of 151cm. It has a light leaf spot rating of 5 and a 6 for stem canker.

Tailor agronomy to help OSR fulfil its yield potential

A “little and often” approach to spring fertiliser applications and tailored use of growth regulators are two important ways growers can help oilseed rape crops fulfil their promising yield potential this season, say Farmacy agronomists.

Low disease pressure and good weed control have resulted in many crops that are well forward, with strong root and canopy growth. Jason Noy, who looks after crops in Cambs, Herts, Wilts and Glos, says the first nitrogen has been applied to some early-sown crops that were beginning to look “hungry”, in order to ensure early development is not constrained.

“This is particularly true in the East where we’ve tended to drill OSR very early in the first or second week of Aug due to flea beetle pressure. Many crops had used up the standard dose applied at drilling, so received 45kgN/ha in early Feb.

“Even further west where OSR hasn’t been drilled so early, crops will benefit from nitrogen if it hasn’t already been applied. We don’t want to generate massive crop canopies, but equally we have to ensure the crop isn’t starved of nutrients.”

The aim with spring fertiliser applications is to achieve a green area index of 3.5 by flowering, and the focus for remaining nitrogen is usually around the stem extension timing. But Jason feels there are clear benefits from holding some back to apply later in the season to ensure the crop is well nourished during the important seed filling stage.

Norfolk-based agronomist Peter Riley agrees, and favours a four-way split, if farm logistics, equipment and product choice allow. The early dose would be followed by another at stem extension (usually mid-March), a third at green-bud stage in early April and a final dose of foliar urea at mid- to late-flowering. “A lot of research shows there are benefits from this kind of approach,” he points out.

“OSR also requires a lot of sulphur, especially when the crop is taking up nitrogen, so I often recommend applying both at the first three fertiliser timings. Sulphur can be very mobile in the soil though so it’s sensible to apply it as close as possible to when it is needed and will be quickly taken up by the crop.”

Additional micronutrients should also be applied as required, with boron in particular often needed – deficiency can impair stem elongation and flowering, he notes.

Jason believes a well-timed growth regulator can benefit large, forward crops and help create a canopy structure that maximises light interception throughout the growing season. Mepiquat + metconazole is his favoured choice at stem extension for growth regulation and height reduction. But he also suggests trinexapac-ethyl can be a useful alternative for canopy manipulation and creating a more even flowering period.

This works by reducing the plant’s apical dominance and encouraging side branches to flower at the same time as the main stem, he explains. “If flowering is less drawn out, it increases the window for light to penetrate the canopy after flowering which helps the plant to build yield potential through photosynthesis.”

Peter advises growers not to get caught out by applying growth regulators too late when crops are growing quickly in the spring. “We sometimes find growth regulators are being applied too late, which reduces their effectiveness. Ideally they should go on at early stem extension, but sometimes they’re not actually going on until green bud stage which is too late.”

Spring disease control should now focus on sclerotinia sprays at flowering, he adds. He favours a two-spray approach including azoxystrobin and boscalid, while prothioconazole-based products are also worth considering, especially if there’s any light leaf spot or phoma to mop up.