What sort of regulatory environment for new breeding technologies is required and what will be the implication for farmers, and ultimately consumers, who lie at the heart of this debate? CPM reports exclusively on a survey of farmers.

By Tom Allen-Stevens

GM can be a divisive topic, and the farming community is no less split on how and whether it should be introduced as the public in general. Views on gene-editing, however are harder to gauge.

A survey was undertaken in March 2019 by the Gene-Editing for Environment and Crop Improvement Initiative, that represents scientists, breeders and others in the UK agricultural industry with an interest in new breeding technologies (NBTs). The views expressed aren’t representative of farming opinion as the respondents have been selected as those who are relatively well informed on a technology that is, as yet, largely unknown and not commercially available.

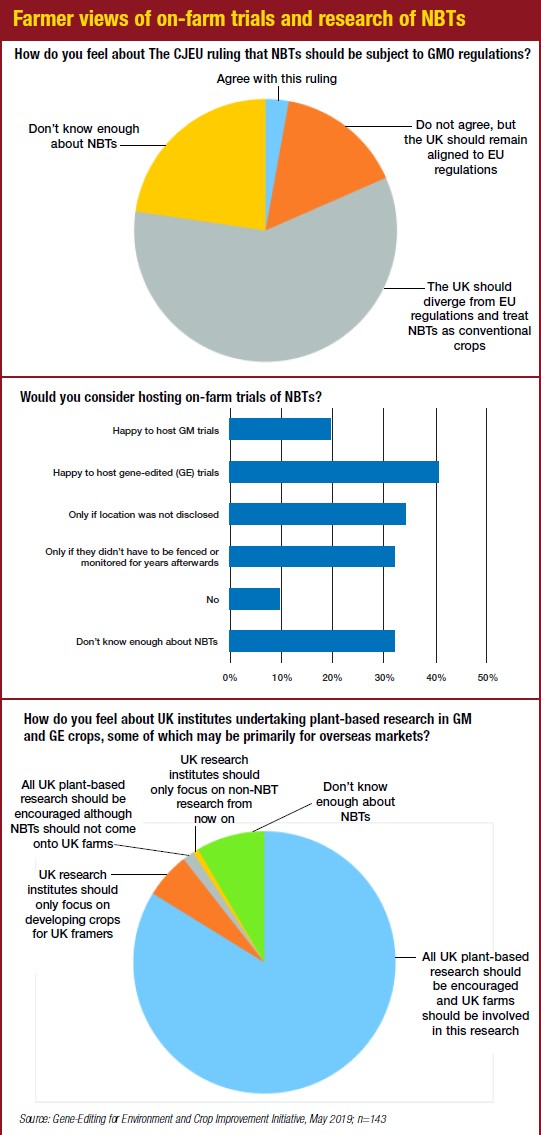

Nonetheless, they are the farmers who, should gene-edited (GE) crops be grown commercially in the UK, are likely to be the first to have the opportunity, and the survey reveals it’s one they’d be very keen to explore. Almost three-quarters disagree with the Court of Justice for the EU ruling classing GE crops as GMOs, although 16% feel the UK should remain aligned to the EU. Just 4 of the 143 respondents agree with the ruling.

Nonetheless, they are the farmers who, should gene-edited (GE) crops be grown commercially in the UK, are likely to be the first to have the opportunity, and the survey reveals it’s one they’d be very keen to explore. Almost three-quarters disagree with the Court of Justice for the EU ruling classing GE crops as GMOs, although 16% feel the UK should remain aligned to the EU. Just 4 of the 143 respondents agree with the ruling.

When it comes to trialling the technology, over 40% would be keen to take part in on-farm trials of GE crops, with under 20% happy to host GM trials. However, around a third of the respondents had grave reservations about doing so under current GMO regulations. These require the location of trial sites to be made public and for the land to be fenced off to prevent ingress by animals and then monitored for years afterwards with any volunteers removed. Significantly, over a third of the respondents, drawn from a relatively informed body of farmers, felt they didn’t know enough about the technology to give an informed response.

But there was resounding support (84%) for the plant-science community to carry out the research needed here in the UK, despite the fact that in the current regulatory environment much of it is likely to end up overseas rather than benefitting UK farmers.

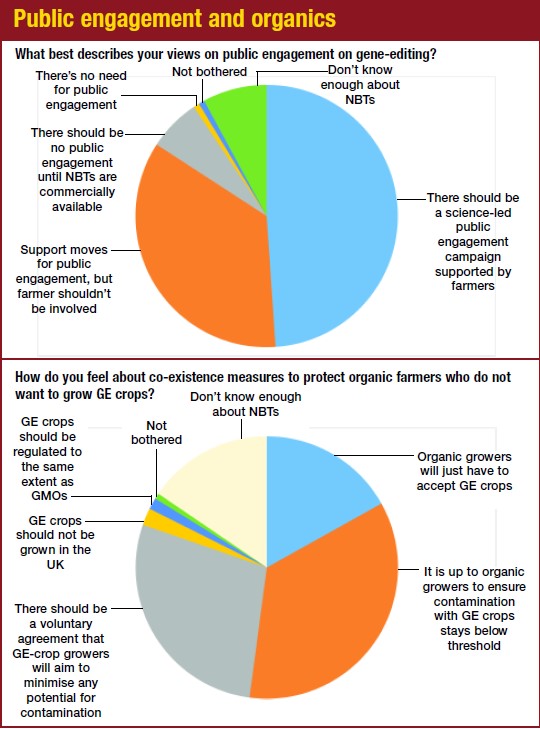

With consumer acceptance likely to be a sticking point, there was overwhelming support for a public engagement campaign from respondents. Almost half of the farmers would like to be actively involved in a science-led campaign, while a further third supported a campaign but felt it was best led by scientists alone at this stage. Just 6% felt there should be no public engagement until NBTs that offer real tangible benefits to consumers are commercially available.

Another consideration is segregation of GE crops. Organic certification bodies, including the Soil Association, have already stated they support the position that NBTs should be treated as GMOs. So GE crops, like GM, will not be allowed to be grown in organic farming systems, which raises the question of whose responsibility it will be to keep crops segregated and contamination below thresholds – under GMO regulations, it is the grower of the GM crop who must maintain minimum separation distances and buffer strips to reduce the risk of cross-pollination with non-GM crops, for example.

Another consideration is segregation of GE crops. Organic certification bodies, including the Soil Association, have already stated they support the position that NBTs should be treated as GMOs. So GE crops, like GM, will not be allowed to be grown in organic farming systems, which raises the question of whose responsibility it will be to keep crops segregated and contamination below thresholds – under GMO regulations, it is the grower of the GM crop who must maintain minimum separation distances and buffer strips to reduce the risk of cross-pollination with non-GM crops, for example.

A third of respondents feel it should be up to organic growers, as they are the ones who would benefit from the perceived marketing advantage. Over a quarter feel a voluntary agreement would be fairer, whereby those who grow GE crops would aim to minimise the potential for contamination. But 17% feel such measures are unrealistic and organic certification bodies will just have to accept GE crops and any contamination issues that may arise.