Mid-October marks the start of the drilling window for blackgrass-affected fields. CPM asks Dr Stephen Moss his thoughts on controlling the weed he’s studied for years.

It’s important for growers to spend time finding a solution that fits their own individual farm

By Lucy de la Pasture

It’s been an epic battle in which the ingenuity of man is pitched against the survival instincts of a grassweed that Bear Grylls would be proud of. So far the weed, which is of course blackgrass, seems to have the upper hand, with human intellect being outsmarted time and time again.

One man who has applied his grey matter to help discover a hole in the defences of this pernicious weed is Dr Stephen Moss. After 40 years of research dedicated to the study of blackgrass, there’s not much he doesn’t know about the weed. So what does he consider the key agronomy pointers that have come from his blackgrass research legacy?

Understanding herbicide activity on a field-by-field basis is fundamental to getting good blackgrass control.

“The main messages on blackgrass control aren’t new but in some places, growers have been slow to adopt changes like delayed drilling and spring cropping, believing that these things were impossible on their soil type. Now these practices are accepted as a means of reducing blackgrass pressure but it’s sometimes been a case of forced change because the problem has become so great,” he explains.

Having been pressing home the same messages for many years, evidently Stephen Moss feels some frustration that some parts of the country are in the position they’re in, but he’s quick to admit that it’s not an easy task to always get things right. So with backs firmly against the wall, where do we go from here with the blackgrass battle?

“Understanding herbicide activity on a field-by-field basis is fundamental to getting good blackgrass control. It’s important for growers to spend time finding a solution that fits their own individual farm and the more time invested, the better the chances of discovering the best tactics in each field,” he suggests.

Even with this field-specific knowledge, the challenge is understanding how the weather also influences herbicide activity, points out Stephen Moss.

“This year has been troublesome for blackgrass control and comparable to that seen in the 2012 season. Trials have shown blackgrass with twice as many heads per plant as normal, which is what’s been causing the challenge,” he explains.

Blackgrass heads which were massively longer than normal were also widely reported from the field this summer, which begs the question why was 2016 such a favourable year for blackgrass growth?

According to Stephen Moss, this is where the over-riding influence of the weather plays a role and he believes the mild weather last winter had a profound effect on the levels of blackgrass control achieved in the field.

“My theory is that a mild winter allows blackgrass plants to recover from residual herbicides. If followed by cool, damp weather in the spring, then blackgrass plants and seed heads continue to grow, which is what we saw this year.”

It’s become normal practice to apply a stack of herbicides to get the desired effect on blackgrass seedlings. After a season like last season, where the control achieved was often disappointing, the value of the herbicide stack can come into question, particularly as post-emergence herbicide performance continues to decline.

Although pre-emergence herbicides can’t eradicate blackgrass on their own, including active ingredients in the stack that haven’t shown any signs of breaking down is a sensible approach, he believes.

“Flufenacet has a strong profile and resistance doesn’t appear to be building year on year as with some other actives. This means there’s a much lower risk of resistance to flufenacet developing quickly,” he believes.

With the arrival this autumn of new post-emergence herbicide, Hamlet (iodosulfuron+ mesosulfuron+ diflufenican), growers may need to watch their rates of DFF and carefully consider which herbicide can play ‘Ophelia’ and sequence with it. A full rate of Hamlet applies 75g/ha of DFF, but if sequenced with 0.6 l/ha of Liberator (flufenacet+ DFF), you’ll be over the typical advisory limit of 120g/ha at which there may be harm to a following oilseed rape crop.

“The recent availability of straight flufenacet options, such as Sunfire, means a stacked programme of different modes of action can be mixed and matched. The advantage is that it provides choice and flexibility for agronomists and growers when considering their approach,” he says.

But it’s important to consider resistance to flufenacet could develop as usage levels increase in the ever-expanding stack and not be lulled into a false sense of security, Stephen Moss warns.

“In trials at Rothamsted, over the past few years we detected a shift in sensitivity to flufenacet in blackgrass populations. So don’t be fooled by the fact that the flufenacet shift isn’t on the same steep curve as Atlantis was. We need to get away from being wedded to the idea that adding to the stack of pre-em herbicides is the answer to blackgrass control,” he adds.

Cultural controls remain central in any blackgrass control strategy, he emphasises. Rothamsted Research was one of the very first to prove that delayed drilling reduces blackgrass pressure.

“This was reiterated in the latest AHDB-funded project I coordinated, which also indicated delaying drilling from mid-Sept to mid-Oct consistently resulted in better control from pre-emergence herbicides.” (see Theory to Field in CPM, Sept 2016 issue).

“Some of our most significant work has also been on blackgrass seed persistence in the soil,” he reflects. Research showed that only 3% of seeds survive being buried for three years, which is crucial knowledge for growers considering ploughing as a method of burying seeds that have been shed on the surface.

“Relatively short-lived seeds are the one weakness blackgrass has and growers must exploit it to win the battle. You can really make a difference over a few years through minimising seed return.

“I’d recommend growers use ‘opportunistic ploughing’ for blackgrass control, which will include ploughing every three to four years, so as not to unearth the seeds when they’re still viable.”

Finding the ideal conditions for effective ploughing can be a challenge, but improving the standard of ploughing, so that full inversion is achieved, is an area where many growers could help themselves achieve better blackgrass control, he believes.

So how does Stephen Moss see his legacy of research into blackgrass being evolved further? Cultivations, drilling techniques and herbicide usage are all areas where he considers there are further discoveries to be made and more research is needed. Understanding more about the biology of the weed will also help pinpoint any further weaknesses that growers could potentially exploit, he believes.

“Issues such as when to use stale seedbeds to reduce the viability of fresh and historic seeds will continue to be an important topic. Drilling techniques for different soil types and the interaction of seed beds with weed control is also an area where advances will continue to be made.

“There’s a lack of good independent research available and the waters are muddied by one-year studies. Farmers could do more themselves to evaluate some of the different approaches that are being put forward as adding to blackgrass control, such as nozzle design and use of adjuvants. These seem to show good results, but may not be statistically significant or are only based on one season’s work so need to be trialled further,” he says.

“It’s also important growers are given accurate information. I often read that blackgrass is a marsh weed. It’s not – it likes damp, wet conditions so maintaining drainage is important but that doesn’t mean it’s a marsh weed!” he concludes.

Percentage perfect

When discussing herbicide programmes, products are frequently described as adding 5% here or 10% there. But there can be a lack of precision when talking about percentages that can lead to misunderstandings about a product’s performance.

Bayer’s new herbicide Hamlet (mesosulfuron+ iodosulfuron+ diflufenican) is a case in point. Most people will have picked up that Hamlet offers 10% greater control of blackgrass compared to Atlantis (mesosulfuron+ iodosulfuron), all of which seems clear enough but what does it actually mean? We asked Bayer’s Dr Gordon Anderson-Taylor to clear things up.

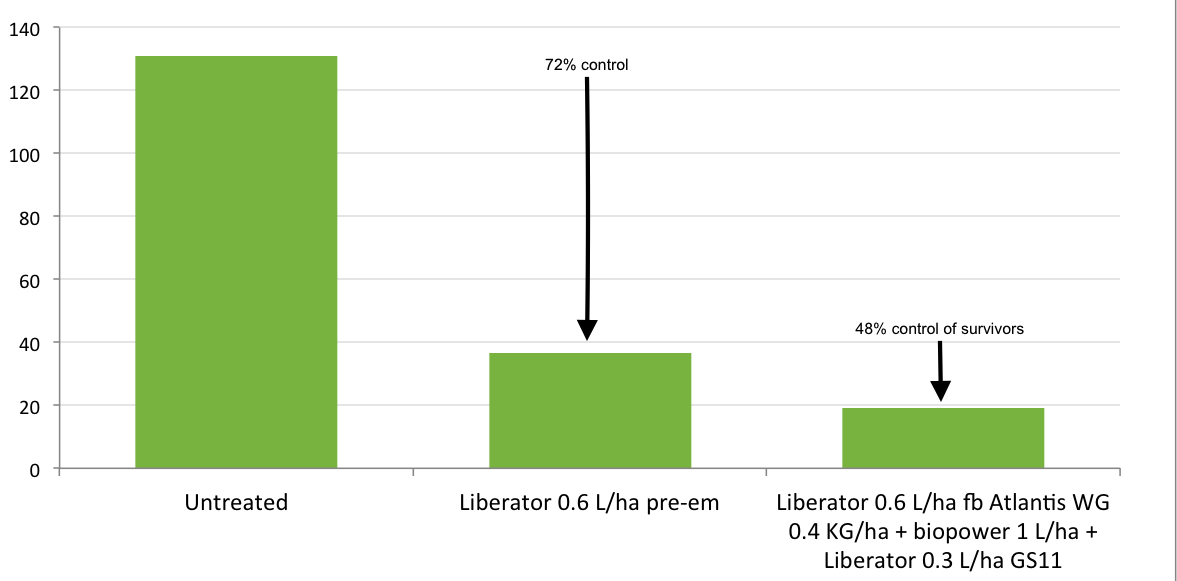

(Y-AXIS – Blackgrass plants/m²) Source: Bayer; results from three independent trials in Essex and Lincs, 2015/16

“Take a simple example and assume that there are 100 blackgrass plants/m², which is made up of a population carrying moderate to high levels of herbicide resistance. Atlantis WG is applied and controls 60 of them, so a simple calculation means Atlantis gives 60% control,” he explains.

So what control will Hamlet give you? “You could see it as 10% more in absolute control in which case control from Hamlet is 70%. But other people may work it out as 10% more than Atlantis and come up with the figure of 66%,” he says, explaining how confusion can occur. “When we compare products in Bayer herbicide trials, we talk about absolute level of control, so in the example we’re discussing the correct figure would be 70%.”

Herbicide programmes are another area where people need to watch how percentages are used according to Gordon Anderson-Taylor. “Each time an additional product is added to a programme, you really need to look at how many of the survivors it controls.”

As an example, a pre-em application of Liberator (flufenacet+ diflufenican) gives 75% control, so out of 100 plants, 25 remain. A programme of Liberator followed by Hamlet gives 90% control so 10 plants remain. Quite often in this situation Hamlet would be credited as ‘offering 15% control’, he says. “But this isn’t quite correct. In the example, Hamlet controlled 15 out of 25 plants that survived the pre-em, which is 60% control of survivors.”

Replicated trials at three sites in Lincs and Essex in 2015/16 with difficult EMR-type resistant blackgrass illustrate the gain from a post-em application.

Untreated plots averaged 131 blackgrass plants/m², those that received 0.6 l/ha Liberator at pre-em averaged 37 plants (72% control), while the plots that were treated with a pre-em and a post-em of Atlantis at GS11 (0.4kg/ha + Biopower 1 l/ha + Liberator 0.3 l/ha) averaged 19 plants, meaning the herbicide programme delivered 85% control in total. The post-em contributed 13% to the total programme but controlled 48% of the survivors, which are the only plants the post-em had the opportunity to control – the others were already eliminated at the time of application, he says.

“In the 2015/16 season, we continued to use Atlantis to test herbicide programmes because we were still waiting for approval for Hamlet when we planned the trials last year,” explains Gordon Anderson-Taylor. “Put these results with the improvements Hamlet offers and we can see that we’re approaching the magic 95% control, even on difficult sites.”

The bigger picture is that there are relatively few options to control blackgrass in the crop, so at all the timings it pays to put the most effective products into the tank because there’s no other way to get that control later on. At the pre-em timing, there’s been a real focus on stacking and sequences, but last year showed how it can’t complete the job, he says.

“I think that people concentrate on the gains at pre-em because it’s perceived as more reliable – but last year it showed its limitations. There were good seedbeds and good application conditions and actually very good control levels from pre-ems. However, the blackgrass recovered because mild winter conditions meant less winter kill of weeds weakened by the pre-em and it then tillered significantly through the spring,” he says, in full agreement with Stephen Moss.

Majority of growers believe they can beat blackgrass

According to a recent survey conducted by Syngenta, UK growers are upbeat about their capability get on top of blackgrass.

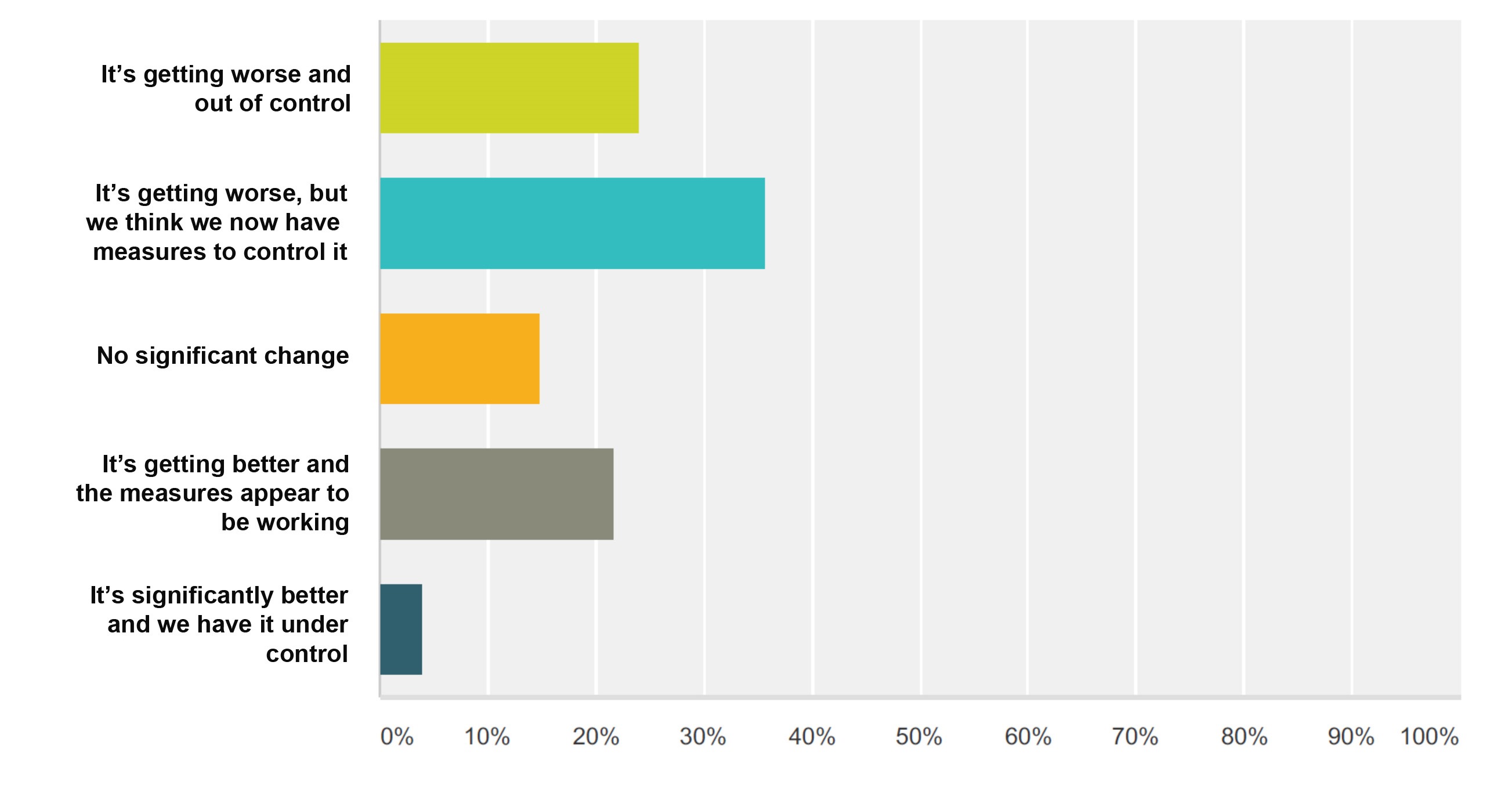

Growers were asked to rank effects out of 10 and blackgrass scored 9.7, with less than 2% of respondents seeing little or no impact on their farm. But encouragingly 75% of farmers now believe they have the tools and measures to get back in control of blackgrass in the future, reports Syngenta’s Cat Gray.

“A quarter of all growers who completed the survey highlighted the situation has actually been getting better on their farms,” she says. “Utilising a range of integrated agronomy tools, alongside an effective herbicide strategy, appears to be paying dividends.”

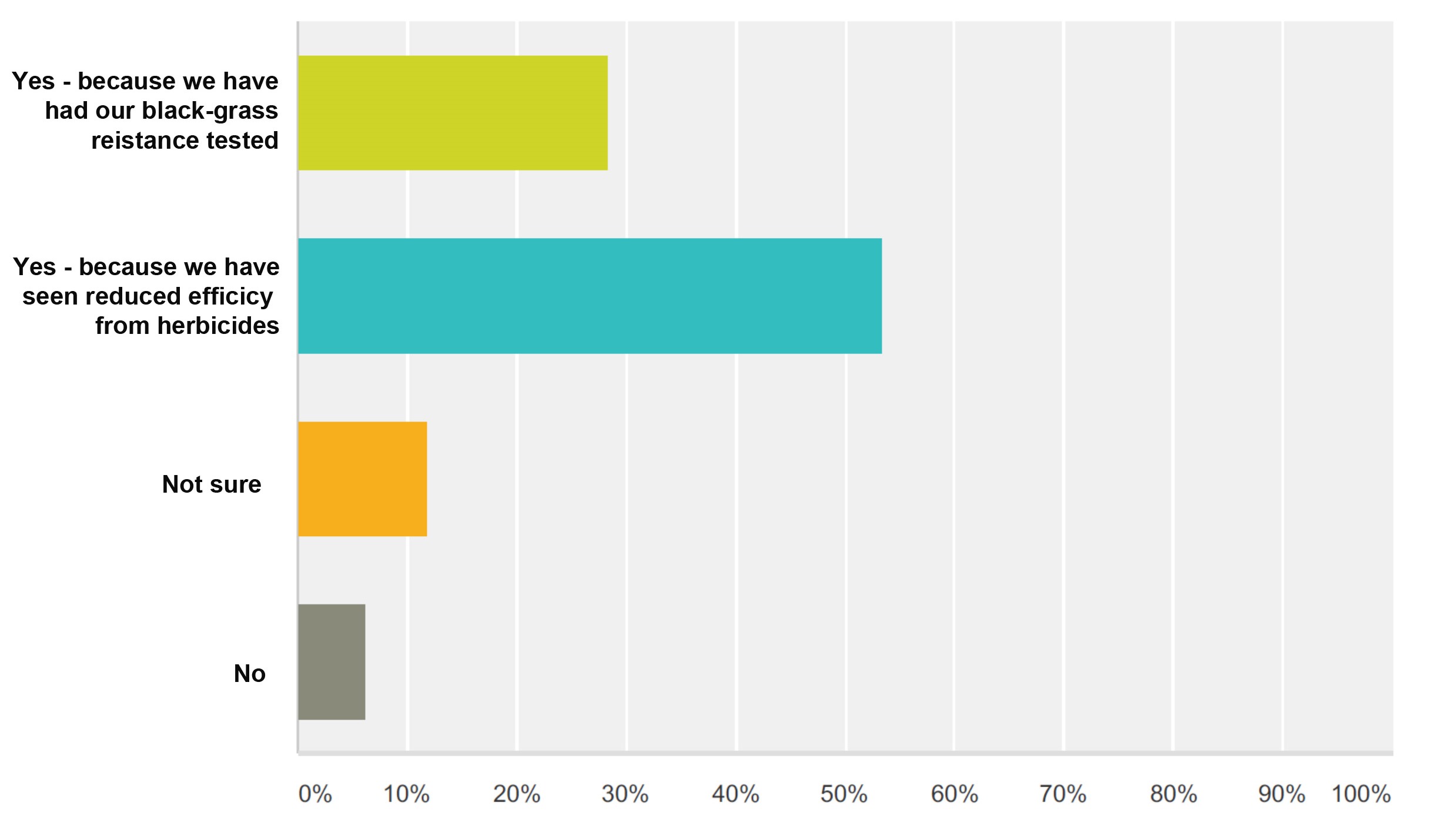

Do you consider you have resistant blackgrass?

Digging further into the methods growers are currently employing, the survey reveals that delayed drilling and growing more spring crops were seen as the most popular agronomy changes, both adopted by nearly 90% of respondents.

There was a perception among growers was that delayed drilling wasn’t having the desired effects on blackgrass populations, with only 23% believing delayed drilling was proving highly effective. On the other hand, 80% of them considered spring cropping was effective or highly effective with 57% of respondents growing hybrid barley in a bid to gain a greater effect on the blackgrass by increasing the crop’s competitiveness.

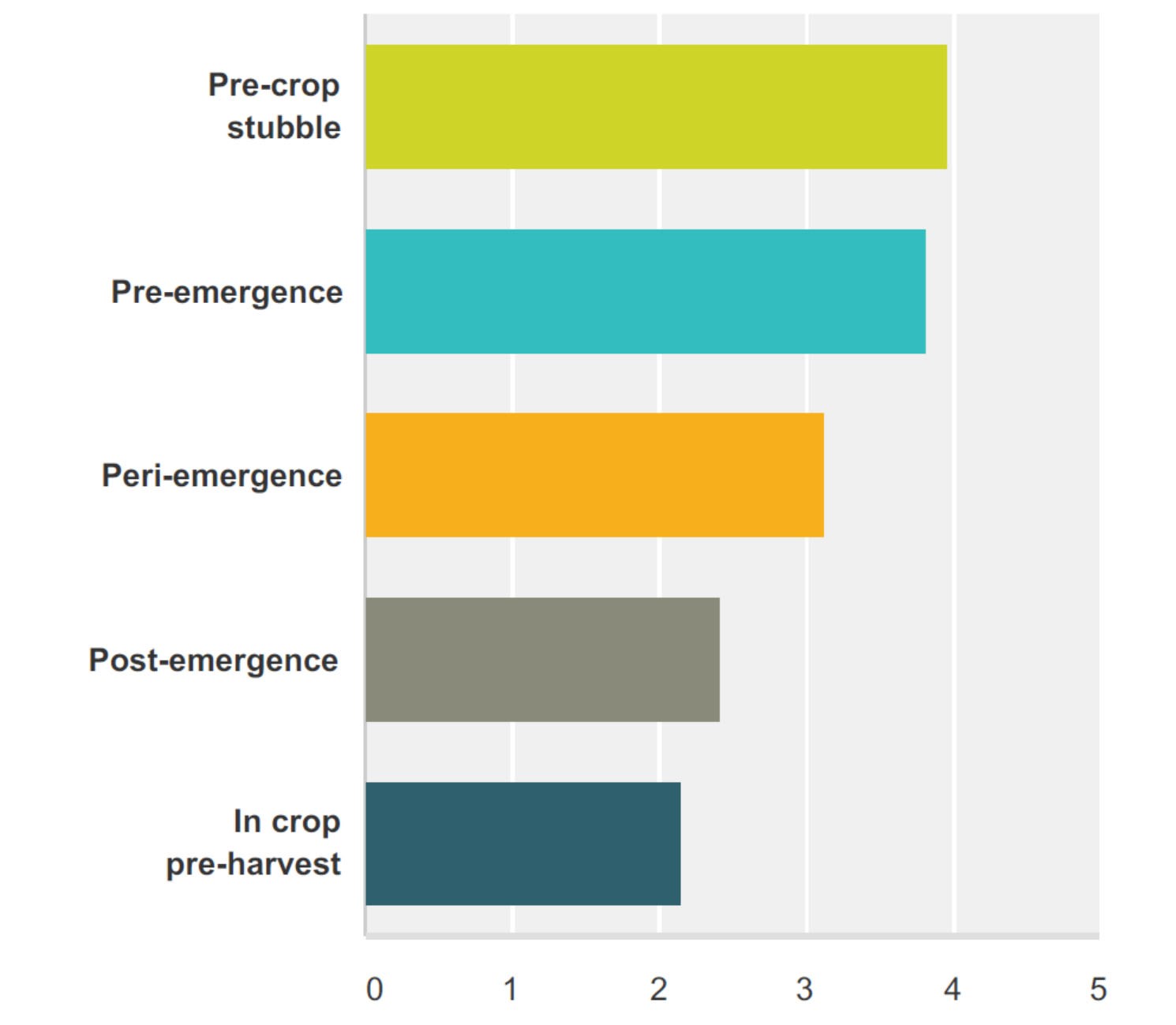

When do you apply your blackgrass herbicides?

Ploughing and rogueing were questioned for their usefulness in blackgrass control strategies. By contrast, sacrificing the crop by applying glyphosate to bad infestations was viewed as a positive move.

“Ploughing is still widely used, on more than 80% of farms. But less than a third of growers see it as effective or highly effective, with 25% believing it has limited value in the overall programme,” reports Cat Gray.

“Rogueing is less popular and is also seen as of limited value, especially when compared with the burn-off of infested crop patches, which over 60% of respondents say is effective or highly effective.

“What’s clearly apparent from the survey is that growers are now using a wide range of agronomy tools in developing a truly integrated approach to long-term management of blackgrass,” she adds.

How would you describe your blackgrass experience over the past three seasons?

Increased herbicide stacking was being used by 85% of growers, with a similar number using increased seed rates to further reduce blackgrass competitiveness and seed return. The report also highlights that over half of growers are now using four or more herbicides in a programme.

Pre-emergence application timing is the most popular, applied by 96% of growers, along with 85% using post-em treatments. Peri-emergence herbicide treatment is least popular.

“Interestingly, while a high number of growers still apply post-em treatments, 59% of them consider the applications of little or limited value,” says Cat Gray. “However, 86% of those using pre-em applications report effective or highly effective results, with just 2% seeing limited value.”

The efficacy of post-em treatments possibly reflect the fact that some 94% of respondents believe they could be suffering from herbicide-resistant blackgrass. However, only a quarter (28%) had populations regularly tested, with the majority reporting anecdotal reduction in herbicide efficacy.

For nearly half of farms (47%) blackgrass is a problem right across the farm. The survey also showed that most growers are now seeking to map the extent of blackgrass populations on the farm, to assess the success of control strategies. The majority is undertaken manually while crop walking, with around 10% of growers now using new technology, such as drones, to further increase accuracy and record keeping.