Using all the agronomic tools available is the best way to tackle LLS. That was the consensus from a cross-industry panel brought together by Bayer to discuss the disease. CPM reports.

You can be reactive with fungicides for phoma infection but with LLS, treatment must be proactive.

By Lucy de la Pasture

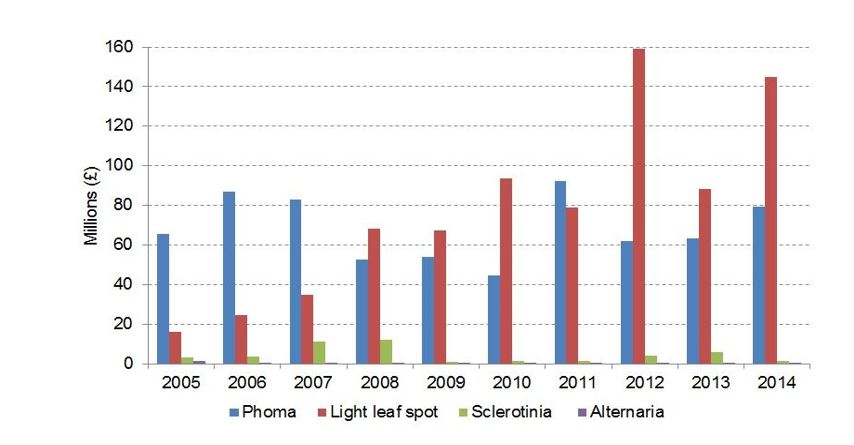

Until recently, light leaf spot (LLS) was a problem for Scottish growers, with little ingress in to more southern climes. That changed a few years ago when LLS became a more widespread problem and in 2008, LLS overtook phoma to become the most economically damaging disease in winter oilseed rape (see chart below). Fera’s Moray Taylor has been analysing data from the Defra-funded Winter Oilseed Rape Pest and Disease Survey to see if an explanation for this can be found.

The survey data is collected each season from around 100 farms in England, with the unfortunate exception of 2016 when LLS spot incidence was very high but the survey didn’t take place.

“The data shows the spread of LLS southwards in the period 2007-2009 and becoming widespread in 2012-2014. Twenty years ago, LLS practically didn’t occur south of the Scottish border, but having analysed potential drivers for this change, there is no clear relationship to explain why this may be. The only ‘almost’ significant factor which may be contributing to the spread of LLS is Feb rainfall, where the data suggests we’ve recently been having a wetter month than historically,” he explains.

For the past few years LLS has been observed sporulating high in the canopy during May.

If climatic factors can’t account for the change in status of LLS in England then various other agronomic factors must be at play, he suggests. So from an agronomic perspective, how can the disease be kept at bay?

Bayer’s Dr Jon Helliwell believes it’s important to build resilience into any strategy to control the disease from the outset, especially where there’s a latent period which makes timing of fungicides all important.

“Use a combination of all agronomics, such as drilling slightly later, selecting a variety that gets away quickly in autumn and spring and utilise LLS-resistant varieties. Above all, get an LLS-active fungicide spray on early in the autumn for best control,” he suggests.

NIAB-TAG agronomist Jon Bellamy nods his agreement, “Yes, it’s just the same as blackgrass control, you have to look at the whole picture rather than looking to fungicides to solve the problem.”

The extent of autumn fungicide application is much lower than perhaps expected for a disease that requires a largely preventative approach, says Jon Helliwell.

“In 2015, just 20% of the treated area received two fungicides in the autumn and only 60% of the OSR area received a fungicide at all. In the autumn of 2016, 9% of the treated area was treated twice and 59% of the crop still didn’t receive any fungicide treatment.”

Warwicks grower, Tom Maynard, chips in that when he grew Incentive (AHDB Recommended List score for LLS is 6), it received two autumn fungicides and further treatments in the spring and he still struggled with disease control until the disease eventually fizzled out.

Winter OSR losses due to disease (£million)

Source: Defra-funded Winter Oilseed Rape Pest and Disease Survey Data.

“LLS is inhibited by temperatures in excess of 20⁰C but is able to grow at low temperatures. In susceptible varieties, the latent period is approximately 30 days if mean daily temperature is around 4oC but can be as short as two weeks if temperature is 15oC.” explains ADAS plant pathologist, Dr Julie Smith.

“Infection requires free water and a minimum of six hours of leaf wetness so the relatively mild wet winters and cool showery spring and summers of late have been conducive to disease development and allowed the pathogen to cycle throughout the season. For the past few years we have observed actively sporulating LLS high in the canopy in May,” she notes.

One of the factors Jon Bellamy identifies is that fungicides can be pretty variable in controlling LLS, according to the results of NIAB-TAG trials. He highlights timing as being critical.

“You can be reactive with fungicides for phoma infection but with LLS, treatment must be proactive. But even the best products for LLS can be variable due to factors such as resistance, timing, crop resistance rating and conditions at application.

“Prothioconazole is the best active for good control of both diseases with Refinzar (penthiopyrad+ picoxystrobin) a close second. An early application of plover (difenoconazole) will be good on phoma but will at best only give some protectant activity for LLS. Tebuconazole isn’t bad but better suited to a spring application as rates required might be too hard on the crop in the autumn,” he says.

“We’re losing Refinzar after this year and that leaves us perilously short of different effective actives for LLS control. As far as a proactive strategy goes, this approach soon becomes compromised in a blackgrass situation where a clethodim treatments to take out young blackgrass plants takes priority and cannot be tank-mixed with a fungicide.”

The double whammy is that sequencing treatments isn’t an easy affair, with a period of 14 days either side of a clethodim application required before a fungicide or another herbicide can be applied. Consequently, autumn fungicides are often applied together with propyzamide in Nov, with the additional compromise of when travel is possible.

The trouble with this approach is that most fungicides are only effective when a pathogen is no more than half way through its latent period, Julie points out.

The latent period is governed by temperature and leaf wetness, being approximately 10 days at 16⁰C and 12 days as temperature increased to 20⁰C. The latent period then lengthens as temperature decreases – 12, 17, 20 or 26 days at temperatures of 12, 8, 6 or 4⁰C respectively, explains Moray.

A further complication at the Kerb timing is getting a dry enough leaf to apply the fungicide to, adds Jon Bellamy. “Ideally fungicide should be applied as a separate treatment for most effective LLS control.”

Tom believes resistant varieties play a key role in controlling LLS infection. The disease is a problem on his farm and variety selection is top of the list as part of his overall control strategy.

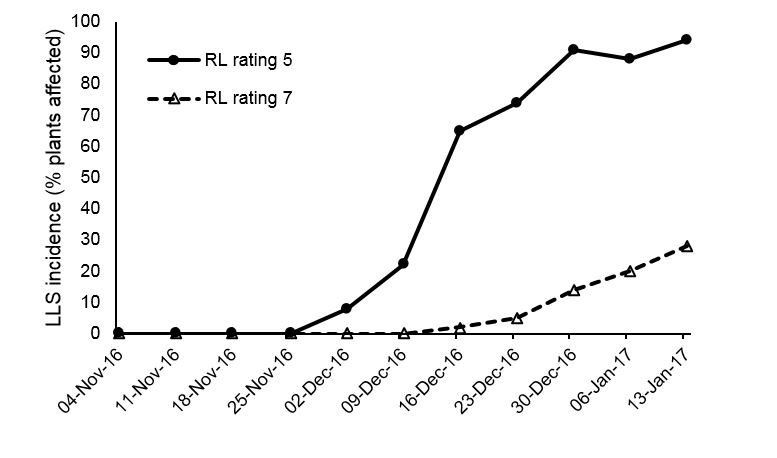

Disease incidence as % of plants in a crop affected by LLS in 2015-16 season.

Source: ADAS Rosemaund, Herefords.

“I select OSR varieties with a RL score of 7 for LLS, a 6 isn’t enough, and it has made a difference to control,” he says, adding that this autumn he has Nikita, Flamingo and Elgar in the ground.

Julie agrees this is a good strategy, explaining that a resistant variety will effectively shift the epidemic by extending the latent period, giving a wider and more flexible spray window to apply fungicide (see chart above).

She points out that sometimes in trials there’s a phenomenon where highly-rated LLS resistant varieties can look clean over winter but appear almost as diseased as the more susceptible varieties in late spring. So to what does she attribute this apparent ‘break-down’ in the resistance of the variety?

“I believe the resistance mechanism is still functioning so it’s most likely due to disease escape traits via spring vigour and rate of stem extension. If a variety is slow growing in the stem extension phase, then plants remain ‘squat’ for longer in a microclimate where conditions are favourable for the disease to keep cycling because spores have only a small distance to splash onto clean leaves, providing continuous infection.

“If the rate of stem extension is rapid then the distance between infected and clean leaves or buds is greater for spores to jump and the plant can effectively escape a proportion of new infections. I also believe that disease tolerance has a role to play. Tolerance is distinct from resistance and we define tolerance as the ability of a plant to maintain yield in the presence of disease.

Julie clarifies that a resistant variety expresses a low level of disease, where as a tolerant variety becomes diseased but is still able to maintain a high proportion of its yield potential. “Theoretically it should be possible for breeders to select for and introgress both into the same variety as they are complimentary,” she says.

Jon Bellamy believes that the distinction between a variety’s resistance and its tolerance to LLS is an important one. “Resistance shifts the epidemic whereas tolerance is how a measure of the extent a variety is affected by an infection,” he says.

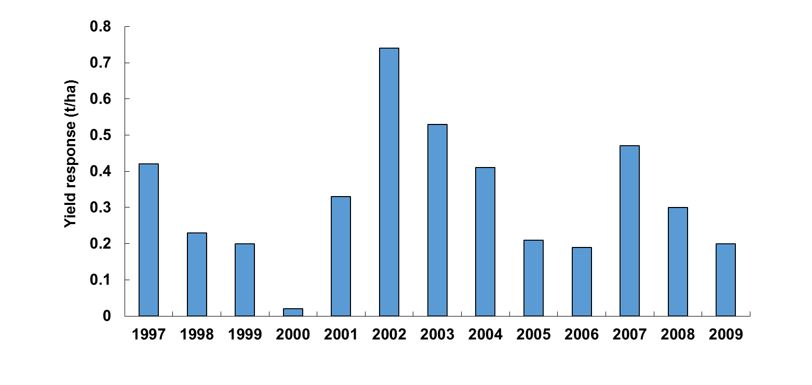

Yield response to two autumn fungicides, 1997-2009

Source: ADAS Boxworth, Cambs.

Variety tolerance is an area Julie would be very keen to look at in OSR, where this work hasn’t been done. “We’ve investigated disease escape and disease tolerance using the septoria winter wheat pathosystem and the results show that both traits can make a significant contribution to disease management and maintaining yield. Integrating these novel approaches would help to protect our resistance genes and chemical actives,” she says.

Jon Bellamy agrees that this would be useful information to have in the field. “There may be OSR varieties that are very tolerant to LLS as well as resistant,” he adds.

So what approach do agronomists currently take to control LLS? “While agronomists drive the spray decision for LLS, in OSR there isn’t the same sort of planned fungicide strategy as in cereals, other than a fungicide spray in autumn, stem extension and early to mid-flowering,” says Jon Bellamy.

“I aim to target both phoma and LLS in the autumn but when two sprays are required, there’s always a question mark over whether the second spray will go on.”

Tom says that travelling in the autumn over the 280-365ha OSR he farms is often a limiting factor for him. Because LLS is a problem he uses resistant varieties to give him added flexibility on spray timing.

Jon Helliwell adds that in Scotland where single sprays are used in high LLS pressure situations, keeping rates at 75-100% dose of Proline (prothioconazole) is the norm. But Bayer trials data continues to back up a two-spray strategy in the autumn as being the most effective strategy.

“If the second application doesn’t go on then you’re completely reliant on the first spray. That’s why we suggest using a robust rate of prothioconazole as the first spray to give some longevity of control and activity on both phoma and LLS,” he explains.

So should we be moving towards a two-spray autumn fungicide programme further south? Jon Bellamy presented data from a recent review of all the NIAB-TAG trials data for phoma and LLS in the period 2007-2016.

“Of the 158 treatments, 73% show a positive yield response to autumn fungicide applications. The average yield response is 0.19t/ha which at first sight looks disappointing, but the range of responses across the treatments is huge, with a maximum yield loss of over 1t/ha.

“The LSD is 0.44t/ha, so there’s very little significant differences in the figures, we’re only talking trends here. But what the data does show is that even though the range of marginal responses is huge at +/- £250, it’s risky to do nothing. To protect the crop against a possible 1t/ha yield loss justifies a fungicide spend of £30/ha,” he comments.

ADAS trial data shows a similar range and variability in yield responses (see chart above), confirms Julie but she believes that treatments applied when LLS symptoms are first seen can make a big difference.

“Even low levels of LLS can be quite damaging, and 3-5% infection shouldn’t be overlooked. Where LLS has appeared in susceptible crops (rated 5 or less on the RL), we’ve seen infection levels rise from just 3% to nearly 70% in a period of 10 days. The polycyclic nature of LLS means there’s continuous infection under favourable conditions so the disease can escalate very quickly.

“As a rule of thumb, 15% of plants affected at stem extension results in a 5% yield loss and we have seen 0.25t/ha losses without LLS being noticeably present on the pods of plants. When infection reaches the pods, then seed loss can be greater due to premature ripening and pod shatter. LLS can also cause physiological effects such as twisting of leaves, stem cracking, stunting, flower bud deformities and flowers that don’t open properly,” says Julie.

The data from both NIAB-TAG and ADAS also show that autumn/early winter treatments give a strong response to fungicides, in line with Bayer trials work.

Early disease control vital

Early control during Oct, supported by a follow-up spray later in autumn is widely regarded as the most effective way to tackle phoma and LLS, says Hutchinsons’ Dr David Ellerton.

“Phoma infection must be stopped before it reaches the stem otherwise it’s virtually impossible to control and will result in stem cankers later in the season. Priority for fungicide sprays should be given to small plants of susceptible varieties where the distance for the mycelium to travel to the stem is shorter and therefore quicker.”

A routine protectant spray for LLS in late Oct or early Nov is worthwhile, particularly on susceptible varieties. There can be long periods of symptomless growth, so do not assume crops are “clean” if no disease is identified.

LLS symptoms are often not found until late Nov or Dec, by which time the disease may have already spread within the crop ready to build quickly when conditions are suitable. There is no threshold for LLS as prevention is better than cure.

Northumbs-based agronomist Tom Whitfield says a preventative spray during Oct is particularly valuable in areas or soils where it is hard to travel on fields later in the autumn.

“Early Oct is the main window for a protectant spray. There will inevitably be a lot of phoma around by this time and even if LLS symptoms aren’t visible, infection is likely to have occurred.”

Fungicide choice is determined by the disease risk and any need for growth manipulation, says Tom.

“If phoma reaches the 10% threshold, an appropriate fungicide is needed regardless. If the variety is weak against LLS or other diseases and/or requires growth regulation, then product choice should be tailored accordingly.”

Where disease control is the priority, David advises basing fungicides around triazoles such as prothioconazole, tebuconazole, metconazole, prochloraz+ tebuconazole, difenoconazole or the SDHI plus strobilurin option of Refinzar.

Difenoconazole, metconazole and tebuconazole are weaker against LLS while prothioconazole is particularly strong. Strains of LLS have been identified with reduced sensitivity to triazoles and in this case a non-triazole is a strong option against both diseases.

Where growth manipulation and disease control are both needed in more forward or thicker crops, then metconazole or tebuconazole-based products are more appropriate.

An alternative in particularly thick, forward crops is a growth-regulating product based on metconazole and the cereal growth regulator mepiquat chloride, which has clearance for autumn application in forward crops. For maximum benefit, it should be applied from the 4-6 leaf stage to actively growing crops during Sept/ Oct.

In more backward crops, or those on particularly light land, then Refinzar would be a good choice. Trials have shown excellent phoma and LLS control combined with an ability to considerably increase root mass enabling better nutrient uptake and potentially better growth in a dry spring, through increased water scavenging. Uniquely, this is achieved without reducing crop size above ground.

Withdrawal of Refinzar

CRD issued a withdrawal notice for products containing picoxystrobin, which includes OSR fungicide Refinzar, on 23 Aug 2017. The notice states the reason for the withdrawal being due to the non-renewal of approval of the active substance picoxystrobin, under implementing regulation (EU) 2017/1455. Refinzar won’t be available for sale by the approval holder (DuPont) on 30 November 2017 and sale and distribution of existing stocks ends on 31 March 2018. The period for disposal, storage and use of existing stocks expires on 30 November 2018.

Optimising blackgrass control using Kerb

Blackgrass is an ever present and continuing threat, it’s important to keep an eye on the ball, says Dow AgroSciences’ Peter Waite. That means making the most of the opportunity to control blackgrass throughout the rotation particularly making the most of OSR, which is the only significant break crop where this control option is available.

“There is no known resistance to propyzamide, so Kerb Flo 500 (propyzamide) or Astrokerb (propyzamide+ aminopyralid) offer a chance to manage blackgrass populations ahead of the following cereal crop,” he says.

To get the best out of products containing propyzamide, Peter points out some essential principles to bear in mind when applying.

“Keeping propyzamide in contact with blackgrass roots for as long as possible is the number one aim. Cultivation strategy can have a bearing on this, with no till and min till strategies generally working best as they retain blackgrass seed in the top 5cm or soil of the soil profile where most propyzamide is retained.

“Soil temperature influences the length of time propyzamide is retained, in cooler soil temperatures retention is longest which gives germinating blackgrass a longer opportunity to take up a lethal dose of the active, hence the recommendation to apply when the soil temperature is 10⁰C at 30cm depth. Adequate soil moisture for uptake is also important and these optimum conditions for application are rarely reached before Nov,” he explains.

The weather data webtool that provides a traffic light indication of when conditions are suitable for propyzamide application is already familiar to growers but it has been revamped for this season, points out Peter.

“The tool now has added rainfall and wind speed predictions to help growers plan applications by indicating possible spray windows. It’s important to think about the risk to water before applying and try not to make applications if significant rainfall is predicted within 48hrs of application.”

The weather criteria are simply a guide, he emphasises. “Propyzamide can be applied earlier, it just won’t last as long in warmer soils. Situations where this may be the preferred course of action are when the primary target is broadleaf weeds.

According to work done by Dow, if a graminicide hasn’t already been applied and the grower is presented with a very dense population of blackgrass, then control can be further optimized if propyzamide is applied together with Laser (cycloxydim), says Peter.

In a year where OSR crop canopies have developed well, there’s an added temptation to go early with a propyzamide application, but this isn’t necessary, he believes. “Even if the crop has a full canopy, the herbicide will still reach the soil and efficacy will be the same. We carried out a canopy removal trial which showed no significant difference between Kerb efficacy when applied to a full intact canopy or where the canopy was removed prior to application.”