Faced with poor harvest prospects, a market knocked by COVID-19 and trade deals threatening to undermine UK production, the mood in many of the business webinars at Cereals Live ranged from sombre to indignant. CPM reports.

By Tom Allen-Stevens

As the row over food standards reached fever pitch, it inevitably dominated many of the webinar sessions and discussions at Cereals Live last month. Farmers and industry leaders may not have been able to gather in person, but the passion was palpable, the messages clear and what came through was a real sense of urgency for some of the major issues facing the arable sector.

Farming minister Victoria Prentis faced criticism for not appearing in person for her webinar slot. Instead, she delivered recorded messages both for the webinar and in response to three questions submitted before the event by CPM. But during a live press briefing, she strenuously denied suggestions Defra had been instructed not to engage with farmers as a result of the NFU food standards petition that was rapidly making its way to one million signatures. The session had clashed with a crucial vote in the House of Commons, she explained.

But she was clear that standards would not be compromised through trade negotiations. “As we leave the EU, we have brought over existing regulations and will maintain the same import standards. We are absolutely committed to high standards in UK Agriculture and that will not change,” she said.

The aim of the Agriculture Bill is to reward farmers for providing public goods and producing food, said Victoria, but this had “got conflated” with trade issues. “Legislation is not the answer to address food concerns in trade negotiations,” she said.

Although the minister indicated she didn’t feel a food standards commission, suggested by the NFU, was necessary, international trade secretary Liz Truss has since agreed in principle to the move. The Trade and Agriculture Commission will be set up by the Department for International Trade (DIT) on a time-limited basis to ensure free-trade agreements don’t undermine UK farmers and to advance higher global standards through the WTO.

It was on the future of oilseed rape that much of the political discussion hinged. UK rapeseed production this harvest is set to dip below one million tonnes – just half of domestic consumption and around 40% of production five years ago. With cabbage stem flea beetle cited as the main cause, Victoria rejected an NFU suggestion of a scheme to alleviate some of the risk for growers. “We don’t consider a government scheme to underwrite the crop to be an effective way of supporting good agricultural practice or in fact the crushing industry,” she said.

She pointed out that the issue of rapeseed imports produced using neonicotinoids, now banned in the UK, predated Brexit. She also agreed that trade policy currently doesn’t address the problem of off-shoring production of commodities at standards below those accepted in the UK.

“Do we have regulations that currently protect us against standards such as on chlorine-washed chicken and hormone-treated beef below which we will not go? Yes. Do we need to include other standards? Very probably in the future. It is quite wrong to export environmental ‘bads’, but we cannot address everything in the context of the Ag Bill,” she said.

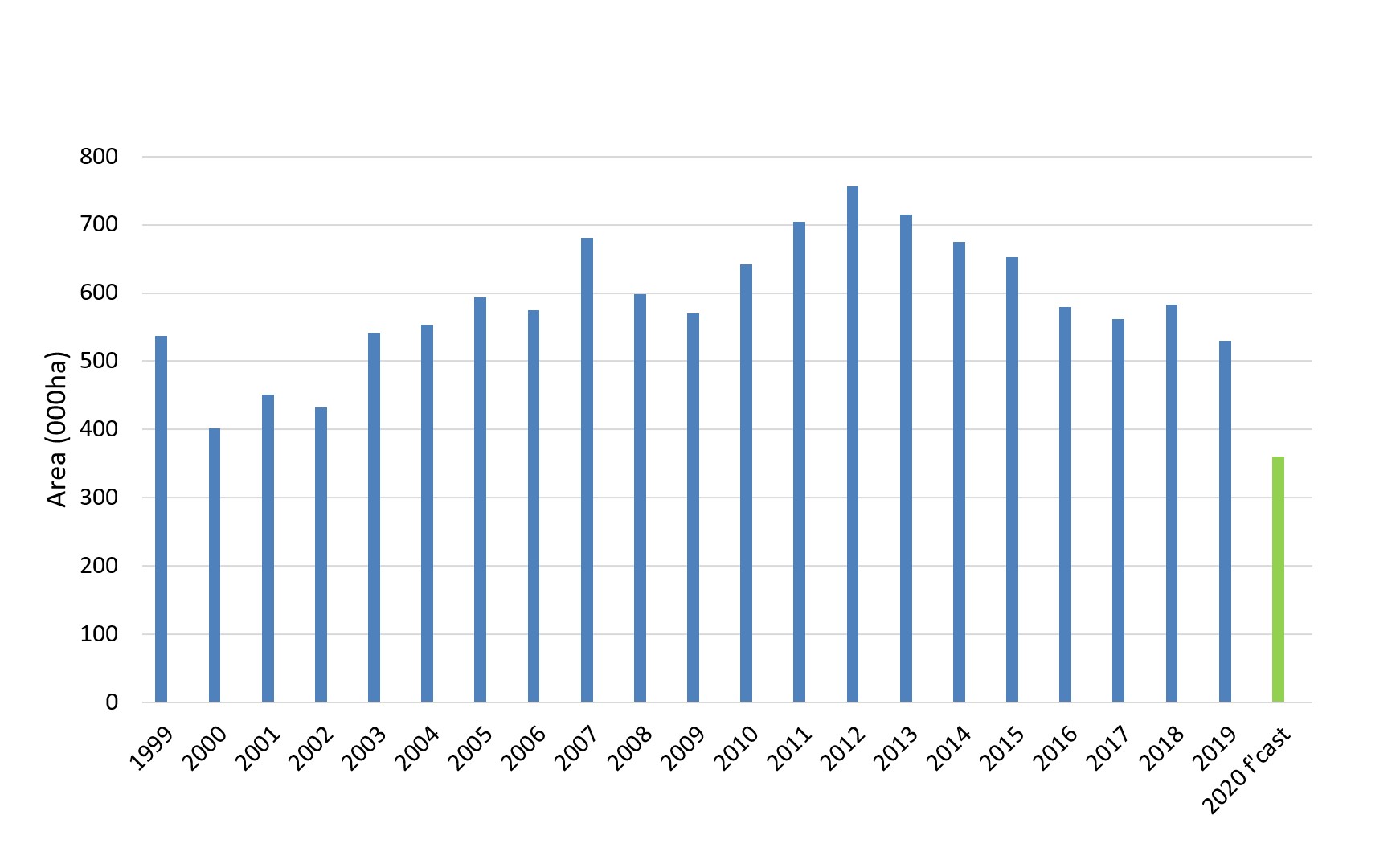

UK oilseed rape area

Oilseed rape is fast becoming a niche crop. Source: NFU

But NFU agri-food policy delivery manager Jack Watts said Defra was “in a state of denial” over OSR. “It’s the elephant in the room – the demise of OSR is one of the biggest problems in the arable market. We’ll see a continued exit from the crop as growers cannot cope with that level of risk.”

Martin Farrow of ADM, the UK’s biggest rapeseed crusher, pointed out the reduction in production, and resulting supply deficit are occurring across the EU where (unlike the UK) 65% of demand is used for mandated biodiesel.

“Importing is not a good option for us in the UK,” he said, explaining that where there is an exportable surplus in the world it is either GM, such as from Canada, or from regions of unreliable weather, such as from Australia. “The crushing industry is entirely set up for UK production. We need UK farmers to grow OSR, and without it, the current structure of the industry is not sustainable.”

NFU president Minette Batters warned there would be environmental as well as sustainability issues for farming if OSR continues its trajectory and becomes a niche crop. “We feel very strongly about the importance of flowering crops and making sure we have stability in our rotations,” she said.

“OSR has been massively undermined by imports produced using neonics that we don’t have access to here. If we’re going to keep this high-cost regulatory framework, OSR imports into this country are going to have to be produced to those same standards. They should play by our rules. We are continuing to off-shore our production.”

The million signatures on the food standards petition showed it’s not just farmers who have concerns, she pointed out. “This is about real people who really care about food standards and want to make sure our farmers are not undermined.”

Following the announcement of the Trade and Agriculture Commission, three weeks after Cereals, Minette said this “hugely important development” was something the NFU had been requesting for over 18 months. “It will be vital that Parliament is able to properly consider the Commission’s recommendations and can ensure government implements them effectively.”

The move may help progress what Minette sees as an opportunity for “building back better” as the nation recovers from COVID-19.

“We have a real opportunity to transform the transparency and the implementation of regulatory and private standards associated with imported grain. We’re doing great things but must be able to evidence it. This will become increasingly important as we go into the world of public money for public goods, that we are able to show the world-class sustainable farming practice we have here.”

Central to this lies “the challenge of our time”, said Minette – producing carbon-neutral food by 2040. “It’s been fascinating to see the data on clean air during lock-down and many journalists pointing out that farming is not the problem after all. I really want to put farming as the solution in all of this.”

The UK has the opportunity and the evidence base to show leadership on how to farm sustainably, she maintained, and this will become a “big factor of trade” going forward. “But to achieve this, we’ve got to be able to have world-class farming businesses. We must focus on the core business and not the periphery of our farms and not just stewardship. Climate change, achieving net zero is a real anchor point for UK agriculture to be globally ambitious and to provide that leadership.”

Risk reduction may drive decisions

There’s a risk that maize will undercut the feed cereal market, according to AHDB senior market analyst David Eudall. He’s taken a look at maize and the implications of removing the tariff on imports, as proposed by the UK Global Tariff, which comes into effect on 1 Jan 2021 as UK policy diverges from the EU.

“To get maize from Ukraine delivered into a UK feed mill, that currently works out at around £190/t. Feed wheat is trading well below that, so there’s no reason to bring in maize,” he says.

“After harvest, we’re expecting a cheaper price for maize – around £175/t delivered for Sept, and UK feed wheat is trading around £176/t delivered. So that’s setting the price for domestic grain – import parity.”

Take off the current €10.40/t tariff, applied under the EU’s Common External Tariff, however, and imported maize drops to £167/t. If the £ recovers from its current weak position, David estimates an even cheaper price, at £160/t, based on market values at the time. “So there’s a real price risk as we go forward.”

Irrespective of the effect of maize, farm business consultants Andersons warn that arable profits will take a heavy hit in 2020 from a vastly reduced harvest. Cashflow problems will start to kick in this autumn and next spring as growers look to fund the new crop with poor harvest returns.

Its Loam Farm model, with 600ha of combinable crops, shows a loss of £27/ha before basic payment, compared with a profit in 2019 of £115/ha. With OSR gross margins declining for the past few seasons, the decision’s now been taken to drop it from the rotation altogether in favour of a greater area of spring crops.

But Andersons’ Sebastian Graff-Baker notes growers with an understanding of “the mosaic of profit” could identify areas of land with consistently low yield and take them out of production altogether. He believes 10-40% of wheat crops and up to 60% of OSR could be loss-making.

“Countryside Stewardship options AB9 winter bird food, AB8 pollen and nectar mix and AB15 two-year sown legume fallow can bring a gross margin of £300-500/ha, which becomes very attractive, compared with these poor areas,” he notes.

“So we could see a very different type of arable farm – it won’t produce as much food, but it’s less risky and more aligned to Government thinking on carbon sequestration.”