Two new active ingredients expand the options for chemical control this autumn, but growers would be foolish to rein back on cultural measures, warn experts. CPM reports.

Removing a significant control such as delayed drilling will mean an increase in populations that will continue for several seasons.

By Tom Allen-Stevens and Rob Jones

Additions to the autumn herbicide stack these days are somewhat rare, so to have two new actives in one year could be deemed a relative treat.

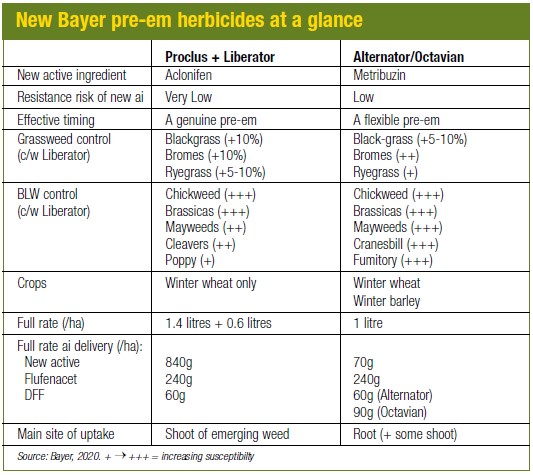

Brand new from Bayer is Proclus, with its new active ingredient aclonifen, while also new for cereals from the same manufacturer is metribuzin. This was released last year in limited quantities, and is now available as Octavian Met or Alternator Met, formulated with flufenacet and diflufenican (DFF).

“A lot of the current actives used in the pre-em stack are in the same Herbicide Resistance Action Committee (HRAC) group and have a similar mode of action,” notes Bayer’s Darren Adkins. “Aclonifen brings a whole new mode of action for broadleaf and grassweeds in cereals, while metribuzin is the first triazinone herbicide approved for use in cereals, although it has been used in potatoes and has EAMUs for some vegetable crops.”

Aclonifen is a true pre-em, a biosynthesis inhibitor taken up by the shoot. Originally discovered by Celamerk and developed by Bayer, it’s been in use in Europe for 20 years and causes bleaching and chlorosis of young shoot tissue as it develops.

New to the UK and to cereals globally, Darren claims the active brings an extra 10-15% control on blackgrass over Liberator on its own, a 10% boost on bromes and 5-10% on ryegrasses. Chickweed and volunteer oilseed rape are its BLW strengths, adding extra activity on cleavers, red deadnettle, mayweeds, speedwell and a mild boost on poppies, cranesbill and groundsel.

It’s a winter wheat pre-em only and is best applied in an even film to the soil surface – it mustn’t be incorporated. “Aclonifen behaves in a similar way to DFF – it’s better in dry conditions than most pre-ems and lasts for approximately two months, so will be picked up when moisture returns,” notes Darren.

Sold as Proclus, this’ll put 840g/ha of the new active on your soil at the recommended rate of 1.4 l/ha. It’ll only be available as a twin pack with Liberator for autumn 2020, with a full co-formulation expected next year. “The cost will be a premium over Liberator on its own – equivalent to adding a product to Crystal,” he says.

Metribuzin has been in use for 40 years, developed by Bayer, and acts by inhibiting photosystem II of photosynthesis, disrupting electron transfer. Resistance exists, but it’s considered low risk, with none reported in grassweeds.

Taken up mainly by the root with some foliar uptake, it adds 5-10% extra control to blackgrass and bromes over Liberator, says Darren. “It’s quite strong on BLWs, especially cranesbill, groundsel and fumitory. As a pre-em it has less slippage than Liberator on its own and at the post-em timing it’s useful for those weeds that have missed treatment.”

This reflects the positioning of Octavian and Alternator. They can only be used at the full 1 l/ha rate up until 30 Sept – thereafter 0.5 l/ha is the maximum rate permitted, delivering 35g/ha of metribuzin. “They’re useful as the pre-em in early drilled crops or as a post-em top-up – we reckon that little bit of contact activity will come in useful,” he says. Like Proclus, the cost of the two new products will be a premium over Liberator on its own.

- Flurtamone has now lost its approval for use and Darren notes that stocks of Movon and Vigon should have used up by March 2020 and cannot be applied this autumn.

Factor in seed-bank dynamics to drilling date decision

Don’t underestimate the difference a cultural control measure, such as delayed drilling, makes to long-term blackgrass control.

While many farmers in the UK have successfully integrated cultural and chemical methods to manage blackgrass populations, Dr Harry Strek of Bayer’s Weed Resistance Competence Centre in Frankfurt, Germany, says a sustained programme involving a number of different measures combined have the greatest chance of success.

“The difficulty is that weed populations take much longer to decline than build up,” he notes. “Resistant populations are that much more difficult to drive down, and removing a significant control such as delayed drilling will mean an increase in populations that will continue for several seasons.”

Weed control is never the same in two seasons, he explains, and generally problems build up slowly, almost invisibly over several years. For resistant populations, most growers only see the increase in the last few years. “Once they become obvious, population and seed return is already very high, which is why a wide range of measures is then required to get them back in control.”

Harry has developed a straightforward model to illustrate the rise of weed populations such as blackgrass. “The idea originated in the UK after a conversation with Dr Stephen Moss who said you needed 97% control to manage down the population blackgrass. That level was based on Stephen’s experience, so I decided to look at these assumptions.”

The model assumes that 10% of seed survives and germinates the year after shed, 1% germinates in the next year and 0.1% in the year after that. “These assumptions are quite conservative but can still lead to rapid growth of weed populations.”

Within the model there’s scope to vary the starting number of weeds and seed return per plant. If there are 1000 seeds/m² in the seed-bank and each plant produces 500 seeds, then total control of 98.2% is needed each season just to keep blackgrass numbers stable, Harry explains. But if each plant only produces 200 seeds then 95.5% control is enough.

“A few per cent extra control over time makes a huge difference, that’s why it’s really important to stack up the cultural options to reach the high levels of control needed. Measures such as higher seed rates or competitive cultivars might not seem to add a lot on their own but that small benefit could be really important. In this context, delayed drilling is too valuable to miss out because it’s such an effective control.”

According AHDB Project Report 560 delaying sowing of winter wheat by three weeks from mid/late-September to early/mid-October reduces blackgrass infestations by 33% on average. In addition, heads and seeds per plant are reduced by an average of 49%. In a field situation, this means that seed return is reduced by two thirds.

The reduction in plant numbers and potential seed return mean that subsequent herbicide treatments have an easier task to control sufficient blackgrass to manage the population. “Stacking up cultural controls gives herbicides a better chance to control blackgrass,” concludes Harry.

Superweed worry from herbicide stacks

Large and complex autumn herbicide stacks could be driving resistance and bringing about superweeds that no form of chemistry will quell, according to research recently published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Communications.

The study, led by Rothamsted Research, was based on an analysis of the Blackgrass Resistance Initiative (BGRI) data. It found that while mixture strategies are very effective at slowing target-site resistance (TSR) to a specific mode of action, they may also encourage non target-site resistance (NTSR).

“We’re not saying that mixtures are bad per-se,” says lead author Dr David Comont. “Rather, we’re highlighting that greater use of mixtures may be selecting for these alternative, broader-reaching resistance mechanisms over time. The drawback to that is that the resistance that they give can be more unpredictable, and potentially affect novel, unreleased chemistry.”

What’s more, the study has implication for other weeds, as well pests and diseases. “Although we’ve demonstrated this in blackgrass, in theory it holds with other species and types of pest too, many of which have also been demonstrated to evolve these types of multi-compound resistances,” he adds.

The Rothamsted team used the blackgrass gathered from farms in the BGRI project to show how the historic use of mixtures of herbicides with multiple modes of action, has altered the type of resistance which evolves.

“We now know that some species can evolve broader, more wide-reaching resistance mechanisms, involving other genetic and biochemical pathways,” explains David.

In blackgrass, these other pathways involve the regulation of multiple genes involved in chemical detoxification, and how molecules are transported and taken in by cells. Changes to these pathways can confer resistance to multiple chemicals with differing modes of action.

In cases where each component of a pesticide mixture can be detoxified by this more generalist resistance pathway, this type of resistance mechanism can be preferentially selected – and therefore spread through the population.

“Mixture strategies will remain a key approach to mitigate resistance, but it’s important to know that even successful strategies like this are not always going to be resistance-proof.

“Future control of pests, weeds and diseases will become increasingly reliant on rapid and accurate resistance diagnostics in order to select the best combinations of chemicals to use, along with the integration of other, non-chemical strategies to slow the evolution of resistance,” David concludes.

Avadex in suspension fertiliser keeps blackgrass at bay

A farming business in Cambs has been successfully managing high levels of blackgrass through mixing Avadex (triallate) with autumn-applied suspension fertiliser.

W R Jackson and Son farms around 2000ha, based at Orwell Pit Farm near Ely on owned and rented land plus contract farming agreements. Soil types range from clay to fen peat, cropping cereals, potatoes, sugar beet and grass for silage and for grazing a herd of 70 pedigree South Devon suckler cows.

While there’s some blackgrass on the farm, it’s under control, says Thomas Jackson, who farms in partnership with his parents, Christopher and Teresa. Only the very worst affected fields are taken out of the arable rotation and replaced with a three-year grass ley.

The business has applied fertiliser from manufacturer Omex in some capacity for its crop nutrition for as long as Thomas can remember. Liquid applications are made through the farm’s self-propelled 36m Hardi Alpha and Fendt Rogator, while suspension fertilisers are applied by Omex contractors Richard Redhead and Matt Benstead.

“We have two or three of our own fields that have concerning levels of blackgrass, although this isn’t surprising bearing in mind the weather we had last autumn,” explains Thomas. “The majority of our fields have either very low levels of blackgrass or none at all.

“Provided you get the Avadex application timing right, very high levels of blackgrass control can be achieved. We’ve been getting excellent results from adding the granules to suspension fertiliser. It gives us an extra percentage of control.”

Previous stubbles are cultivated and sprayed up to three times with glyphosate to produce a stale seedbed. Fields are then drilled and rolled before being treated with Avadex Excel which is mixed in with the suspension fertiliser mix. This is followed by a pre-emergence herbicide, based on flufenacet mixed with pendimethalin or diflufenican (as in Crystal or Liberator) with Defy (prosulfocarb).

“The Avadex is coated on clay which hangs in the fertiliser suspension,” explains Thomas. “Our contractor mixes it in by tipping it into the induction hopper.”

He’s considered other application methods but believes this is more reliable than spinning it on and doesn’t require a separate pass or specialist kit. “It’s so important to get the Avadex to spread evenly and accurately. Using the suspension fertiliser as the application medium is by far the best system and most cost effective too,” he notes.

“But it must be applied pre-emergence of the crop, which does take some organising and also relies on having an experienced operator.”

The application has helped the farm reduce its use of post-emergence herbicides, although if there’s bad blackgrass then it still remains an option, adds Thomas. “Last year we applied it to 200ha before the weather closed in – we’d planned to apply it to a further 16ha. But if we hadn’t applied it with the suspension fertiliser last year, we wouldn’t have many any autumn herbicide applications.” This year he expects to cut back on Avadex use as a result of bringing the blackgrass better under control.