Commercial plant breeders are helping UK scientists develop remarkable new wheat varieties, thanks to a public-funded pre-breeding programme. CPM finds out what’s in store.

CRISPR could cut the time to market from 10-15 years down to just two or three.

By Tom Allen-Stevens

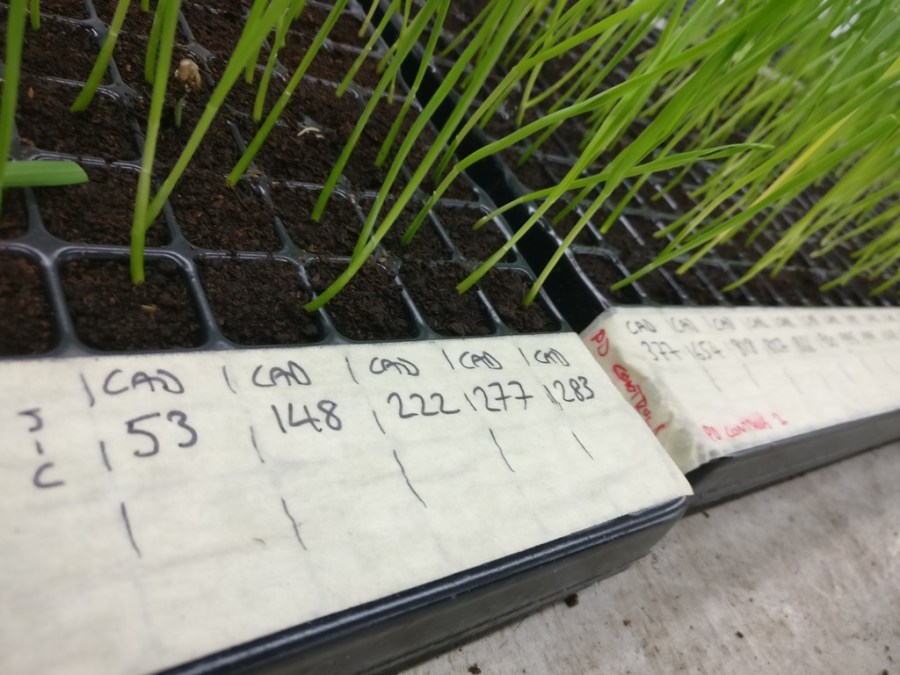

We enter what looks like a large fridge, and there inside are rows upon rows of seedlings, all marked up with a code to identify what they are. There are several with the prefix ‘Cad’, which denotes that it’s one of the mutant lines from JIC, explains RAGT head of genotyping for cereals, Dr Chris Burt. Then there are some other coded lines which are the first-generation crosses.

“We want to get the beneficial trait into an elite variety such as Skyfall. It’s important we use lines we’re familiar with, because Cadenza brings with it a lot of background material we don’t want, that we can then more easily identify and select out in subsequent generations. Of course, in an ideal world we’d have CRISPR mutants and wouldn’t have to take that step.”

Chris runs the genotyping lab at Ickleton, Cambs, one of two operated by RAGT in Europe, the other being in France. Here, winter wheat, winter and spring barley, pasta wheat and triticale are the main crop types pulled apart, scrutinised and annotated. “A trait the breeder spots phenotypically in the field, I want to understand genetically, and develop ways to track it through molecular markers.”

Dr Chris Burt

The material he receives comes mainly from within RAGT, that operates 17 research stations across Europe, servicing the company’s 300 breeders and technicians. “We also analyse other breeders’ varieties – under Plant Variety Rights (PVR) any variety on the EU Common Catalogue can be crossed with our lines to generate new varieties. We also bring in material from further afield, such as CIMMYT (the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Centre, based in Mexico). We’re constantly looking for novel material to enrich our breeders’ programmes.”

He’s looking in two areas – firstly, he uses genetic markers to identify specific genes known to confer traits, such as Orange Wheat Blossom Midge resistance. “We also produce whole genome profiles of varieties and breeding lines. This can be expensive, but it helps us focus in on specific areas of the wheat genome we’re interested in, such as areas we know have a link with yield.”

And that’s what makes these mutant lines of Cadenza particularly interesting to Chris. “This is one area that’s moved on in recent years – there’s now a really good relationship between academics and commercial breeders, and that shows in the material we receive. But we still have to do a couple of years of backcrossing with our elite lines before we have breeding material of any potential value.”

CRISPR potential

There’s then a further 7-8 years of development work to do before they have a commercially strong variety with the trait in National List trials. “CRISPR offers the potential to bring the trait straight into our elite lines, or even into pre-NL1 material, without having to do all the back-crossing to remove unwanted DNA – it could cut the time to market from 10-15 years down to just two or three.”

But the proposed changes to GMO regulations are set to pose huge problems. Not only would RAGT be restricted from making such quick edits to its own breeding lines, it would limit the novel germplasm breeders could introduce.

“It’s easy to test for GM contamination, but gene-edited material is indistinguishable from germplasm generated naturally or through old mutagenesis,” he explains.

“So before introducing new material, we’d need guarantees it didn’t originate from GE lines – the biggest problem would be the time delays in getting the assurances we’d need, which would add to number of years it takes to get a new trait to market. Or we simply wouldn’t use new material, and stick just to varieties of known provenance. But if all European breeders did that, we’d limit ourselves to a dwindling set of alleles and wheat productivity in Europe would stagnate.”