Dow AgroSciences gave a preview of their pipeline fungicide active last month and the trials look very promising. CPM reports.

We’re in a constant arms race between pathogen and product.

By Lucy de la Pasture

New active ingredients are rather like hens’ teeth these days, but a fungicide which also has a novel target site is even rarer. Dow AgroSciences has developed just this, breaking away from its predominantly herbicide pedigree.

Branded Inatreq Active, the molecule (fenpixoxamid) is a member of a new class of cereal fungicides, the picolinamides. Significantly, it will be the first completely new molecule with broad-spectrum activity to be added to the fungicide armoury in over a decade, says William Corrigan, Dow fungicide product manager for UK and IRL.

William Corrigan explains Inatreq Active is the first new broad spectrum fungicide with a new target site in over a decade.

“Inatreq has a unique target site. It’s a Quinone inside Inhibitor (QiI) and inhibits mitochondrial respiration in fungi at the Qi ubiquinone binding site, binding to complex III (the inner mitochondrial membranes),” he explains.

The EU registration dossier was submitted in 2014 and first approval is expected for the new active substance in 2018, for use by UK growers in the season 2019-2020.

At a time when azoles continue to decline in efficacy against septoria and SDHI insensitivity is expected to increase, the new chemistry will be a potential lifeline to our current chemistry, he points out.

“Inatreq shows no cross-resistance to any of the existing cereal fungicide chemistries, including azoles, strobilurins or SDHIs, so will be an essential new tool in an anti-resistance strategy.”

But Dow is keen to point out that Inatreq is also chemistry with a single target site so will also be at a medium/high risk of developing resistance. That means it can’t be viewed as a saviour product and will need to be managed with care from the start, in order to prolong the useful life-span of all three main groups of broad-spectrum fungicide chemistry.

“We’re in a constant arms race between pathogen and product,” adds ADAS principal research scientist, Jonathan Blake. “As we continue to bombard septoria with different modes of action, it’s finding its way around them by evolving and developing resistance.

“Having new modes of action available is essential and using them in conjunction with existing chemistry can slow the development of resistance in other groups. Inatreq is highly active on septoria and appears to be curative and preventative, which is a key attribute in the battle to control the most difficult pathogen we have in UK wheat crops,” he comments.

The new molecule is derived from a natural compound, UK-2A, produced by soil borne Streptomyces species, explains William Corrigan.

The fungicidal effects of the molecule are enhanced by clever formulation technology, adds Dow customer agronomist, Stuart Jackson.

“When the Inatreq spray droplets land on the leaf, there’s a very rapid redistribution across and down the leaf ridges, which translates to exceptional fungicide coverage,” he says.

“Once in the plant, Inatreq is converted back to UK-2A by enzymic activity, thereby activating its fungicidal properties,” he explains.

So how’s it looking in field trials at Wellesbourne in Warwicks this season? At this stage in development, the molecule is being put through its paces alongside the industry standards but not as part of the normal fungicide programme that would be used in practice, stresses Stuart Jackson.

“We’re trying to create a high disease pressure to bring out the differences between treatments. That means we’re using some ‘dirty’ varieties – Torch to demonstrate efficacy on yellow rust and the septoria-susceptible variety Consort. The septoria trial is also being irrigated in the current dry weather to replicate rain-splash events and keep septoria pressure high,” he explains.

In both trials, applications of fungicides were made as a single treatment, GS45 in the yellow rust trial and GS37 in the septoria trial, to a previously untreated crop.

“Although you can’t draw too many conclusions from extreme trials like these, it does demonstrate performance under very high disease pressure,” he says. “In both demonstrations, Inatreq looks to be performing at least as well and in some cases better than industry standards in terms of the amount of green leaf visible in the plots. The next stage will be to look at the place of Inatreq within programmes,” he promises.

The new fungicide is likely be supplied as a co-formulated product and the recommendation will be to apply with a multi-site as part of a robust anti-resistance strategy.

Establishment method has long-term effect

Cover crops are a hot topic. Growing one has been heralded a panacea – helping reduce erosion, improve water retention, add organic matter and generally improve soil structure. There’s also been a huge amount of interest in how they can help with blackgrass control – after all, anything that can help with that is worth trying.

Last spring CPM visited a trial at Newton Purcell in Bucks that compared direct drilling with strip tillage for cover crop establishment. A year on, the longer-term effects are coming to light.

Mike and David Markham, who farm on the Bucks/Oxon border, have been particularly keen to learn more about how cover crops could help them. Their land is a mixture of soil types, with both light soils and heavy clays on the farm.

Unsurprisingly, the heavy soils cause the most headaches, with drainage and blackgrass both prime concerns. They’ve recently moved to a zero-till system, and believe the use of cover crops could become an important part of their regime.

Cover crops can help make drilling a spring crop possible by improving soil structure and drying land out, provided they are sprayed-off at the right time, explains farm agronomist Andrew Richards of Agrii.

“But there’s also a lot of discussion about how they can benefit blackgrass control, so we decided to compare the effects of drilling with a low and higher disturbance drill.”

Cover crops were drilled with a tine drill or Cross-Slot direct drill in autumn 2015. All subsequent crops – spring oats then winter wheat – were drilled with the Cross-Slot across the whole area. The hypothesis was that strip tillage would stimulate blackgrass so it could be destroyed in spring before oats went in.

Blackgrass numbers have been lower where the cover crops were drilled with the Cross-Slot, and even though this field operation took place in autumn 2015, its effects are still apparent in the winter wheat crop which is about to be harvested.

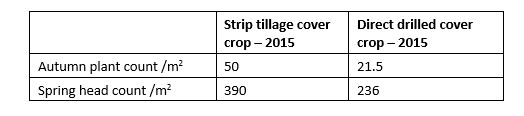

Untreated land assessment of blackgrass numbers season 2016/17

The difference is confirmed by herbicide trials taking place on the farm, with a significant gap between the two strips, irrespective of treatment. Mike and David Markham used 0.6 l/ha Liberator (flufenacet+ diflufenican) plus 2 l/ha Defy (prosulfocarb) plus 15kg/ha Avadex (tri-allate) on the field and the trial results show this was an effective option for this farm as control approached the critical 97% threshold.

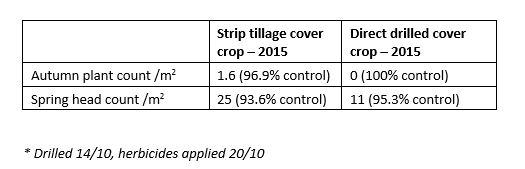

% blackgrass control in herbicide trial, following cover crops

The trial shows the value of cultural controls before you even use any herbicides, says Ben Giles of Bayer. “It shows it’s possible to improve from a difficult situation to a much better one through the judicious use of cover crops, spring crops and establishment.

After the relatively successful cover crops last season, this year has been a more chastening experience, with circumstances conspiring to allow blackgrass to overrun the cover crop. So what went wrong?

“Unfortunately, it’s not always easy to pick the best option but this trial makes the point that stimulating blackgrass germination, to then spray-off, might not make much difference to the amount of blackgrass that germinates in the crop, especially if the seedbank is large.”

One reason was the heavier land on the farm, including the trial field, was mole drained last autumn, following advice from soil and cultivation expert Dick Godwin.

“Over the farm, the land which has been mole drained looks a lot better. In the field where the trial is, the drainage situation was so bad that we double-moled, with four-foot centres rather than the usual eight,” explains Mike Markham.

But the effects of the mole drainage were obvious, with straight lines of blackgrass germinating along the channels. Although the mole channel looks relatively small, pulling the plough through the soil causes fissures and disturbance over a much wider area.

The blackgrass made establishing the cover crop more challenging, which was exacerbated by selective rabbit grazing.

So could blackgrass be used as a cover crop? Not according to Mike Markham. It doesn’t root very deeply, so does little to restructure the soil. On top of that, a thick mat on the surface isn’t easy to drill a spring crop into – pretty much the opposite of what you would want from a cover crop, he says.

To deal with this, he favours spraying his cover crops off early – possibly even Dec or Jan. “This gives time for all the plants to die back, so the sun and wind can dry out the top of the surface before drilling in the spring,” he adds.