By Guy Smith

It’s been a slow start to this autumn’s drilling campaign on account of a long and impatient wait for rain. Having said that I know that for others this autumn has been more the case of a long and impatient wait for a dry window. And just to add a note of congratulation to those of you Goldilocks farmers out there who caught this autumn’s weather just right, neither too wet nor too dry – I’m not at at all jealous of your good fortune. Having written that, I now realise my teeth have become somewhat clenched and gritted while my complexion has taken a hue that could best be described as ‘envy green’.

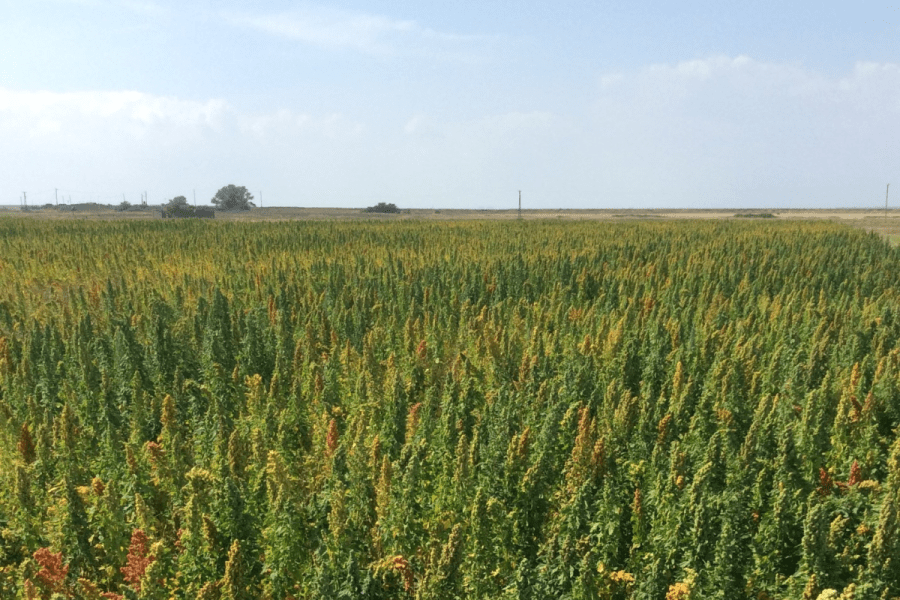

By mid-October my only fields with anything emerged were my August drilled AB15 Countryside Stewardship options. Instinctively it is difficult to generate much enthusiasm for the emergence of a crop that you know will never be harvested but maybe I need to change my mindset. For starters I’ve now learnt to identify things like Trefoil seedlings whereas before I was rather clueless. When it comes to assessing crop emergence, it is still important to know what is from a seed you’ve actually drilled and which is a weed even if you are never going to worry about putting on a selective herbicide. I’ve also taken care to create decent seedbeds as opposed to adopting a ‘chuck it on and hope it comes up’ mentality. If options like AB15 are now going to be regular additions to my rotations, then it makes sense to endeavour to make the most of them even if their financial return has nothing to do with the successfulness of the crop in terms of the measurable end-point of a harvested yield.

This in turn leads into the debate as to whether these various stewardship and SFI options should be assessed in terms of their prescriptions or in terms of their outcomes. With my box ticking hat on I tend to favour prescription rather than outcome. As long as I know I’ve photographed how I’ve followed the rules and that I have kept the seed invoices then I can rest assured I’ve can prove I have done all that was asked of me. My iPhone now has quite a library of some very mundane field activities. On the other hand, with my old fashioned ‘good-stewardship’ hat on there is some pride to be taken from growing a good break crop that delivers what was intended – namely bio-diversity, carbon capture, nutrient optimisation and non-chemical weed control. And not necessarily in that order.

There will undoubtedly be two perspectives on this. The micro-perspective whereby the farmer/practitioner will assess for their selves whether the Stewardship option they have implemented was a success in the field. Then there will be a macro perspective whereby these new national policies will need to be assessed by policy makers. As to whether DEFRA and its various agencies have the wherewithal to make this assessment with robust metrics and thorough methodology remains to be seen. What concerns me is that, like many farmers, I have been involved with various Stewardship schemes for many years. My on-farm view is that they have achieved quite a bit in terms of improved bio-diversity. In contrast I read the latest 2023 State of Nature report to be told that across the piece things are getting significantly worse and farming is to blame. The question is as to whether this will still be the headline in ten years time even if many of us do our earnest best to lock our farming shoulders in the new ELMs scrum.

This article was taken from the latest issue of CPM. For more articles like this, subscribe here.

Sign up for Crop Production Magazine’s FREE e-newsletter here.