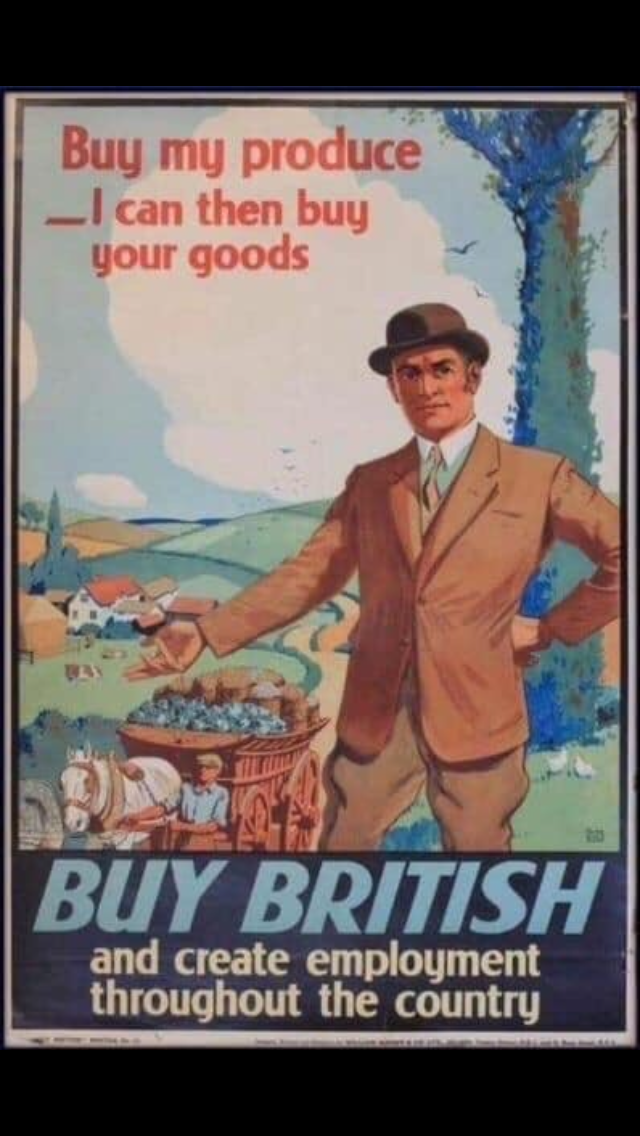

I was struck by this poster I stumbled across the other day from the 1930s.

I was struck by this poster I stumbled across the other day from the 1930s.

Firstly, I was wondering what would be the modern farming equivalent of the then typical farmer garb of hacking jacket, bowler hat, tie and jodhpurs? Clearly, we are a scruffier lot nowadays with tractor-branded overalls being de rigueur on farm. When we are out and about a Schöffel over a check shirt seems to be standard issue. What would our grandfathers think?

Secondly, it’s intriguing that whoever designed the poster felt there was no issue in portraying a farmer as someone who oversaw labourers rather than did much manual labour himself. One likes to think the modern-day image of a farmer is someone hard working who actually drives machinery or physically handles stock. But maybe the spectre of the old moaner leaning out of his Range Rover is not completely dead.

There’s the same common thread of national pride today, but what would our grandfathers have thought of exporting our environmental footprint?

Finally, there’s the rather basic message along the lines of ‘if you buy our stuff then we will buy yours’. Is that still pertinent to today’s world or is it about as out of date as the image portrayed? In the early 1930s as a country we were importing three quarters of our food needs and unemployment levels were over 10%. In contrast today we are 65% self-sufficient and unemployment is at record lows. Today’s messages about promoting British farm produce are all about quality, standards and trust.

If there was a common thread between the promotional messages of today and seventy five years ago it’s probably the appeal to a sense of national pride. You can still find Union Jacks underpinning Red Tractor labels on our supermarket shelves just as the ‘Buy British’ logo fronted 1930s posters. The question is what straplines will appeal to tomorrow’s world?

In a post-Brexit marketing and trading environment how will Britain redefine its place in the world? As we leave what was essentially a heavily regulated but protectionist EU when it came to agriculture, will we need to call for a continuation of that protectionism for our industry? Without doubt a combination of Defra’s high cost regulatory agenda and BEIS’ free-trading globalised view could slowly throttle British Agriculture.

Take the policy around greenhouse gases as an example. If our regulators bring in measures such as fertiliser restrictions to force British arable farmers to reduce their carbon footprint then it’s a fair assumption that we will produce less. If as a result of that we import more of our food needs from places where global warming sits much lower down the political agenda – as indeed is the case in places like the US and Brazil right now – then the net global effect maybe to increase CO2 emissions as farmers elsewhere increase fertiliser use to correct the shortfall produced here.

The point is that national policies must be seen in their global context. We should remember it’s global warming we’re talking about here. There is a clue in the title.

You could make the same argument for pesticides. If Britain bans a pesticide, then if you do not accompany this ban with some sort of trade protection then the net effect could well be the home ban simply encourages the use of that pesticide elsewhere. Our policy makers must always keep an eye on not just what is being done to produce food at home but also what is coming in through the ports to feed the nation.

When you hear the likes of Jacob Rees-Mogg talking up the post-Brexit opportunity to import cheaper food while Michael Gove seems keen to increase environmental standards you realise the farming industry will need to be on its political mettle when it comes to the danger of bogus policies that aren’t joined up.

Guy Smith grows 500ha of combinable crops on the north east Essex coast. @EssexPeasant