Crops that deliver profits year after year tend to come from a diverse rotation designed to meet farming’s challenges and from soils nurtured to perform at their best. CPM seeks expert advice.

For the long term sustainability of your soils, a resilient rotation will help manage the challenges you face.

By Tom Allen-Stevens

Is your rotation fit for purpose? It’s such a fundamental element of an arable farming system, it may seem at first to be a ludicrous question to ask. But a thorough review may reveal your system’s more adaptable to change than perhaps you’d appreciated, and there may be some challenges you’re facing that a little change may go a long way to addressing, according to Stuart Hill of Frontier.

“Weed, pest and disease burdens and resistance, dealing with climate extremes, environmental pressures and legislation, such as the loss of active ingredients and the Water Framework Directive. These are among the major issues, linked to rotation, that growers are up against,” he points out.

Single issues, such as blackgrass, can often drive the need for change, notes Stuart Hill.

“For the long term sustainability of your soils, your farming system and not least profitability, a resilient rotation will

help manage the challenges you face.”

So where do you start? There’s plenty of strong support from the industry to provide information in this area, he says, with recent AHDB-funded projects drawing on historical data to assess rotational impacts on soils and economics.

Single issues

“Rotation is a very broad-ranging discussion, but single issues can often drive the need for change. For many, this has been blackgrass, so Frontier has been looking at this area for five years at our national blackgrass research site at Staunton, Notts.”

The objective of this site has been to review different rotations, cropping and cultivation practice to improve soils and reduce blackgrass populations over the long term.

“There have been some interesting results, and it’s shown the finger of blame for high infestation levels should not be pointed at poor herbicide control – this is just a symptom. What we’ve found is that the root of the problem is frequently poorly structured, compacted, often wet ground that’s in need of some attention.”

As well as the more immediate soil assessment and rectification work, longer more diverse rotations, including

Wheat and oilseed rape may appear to be the most profitable crops, but growing weed, pest and disease pressures are having an impact on yield potential.

spring cropping and cover crops are what’s needed, he says. But it’s a change that’s often resisted because of the perceived drop in profitability that would result.

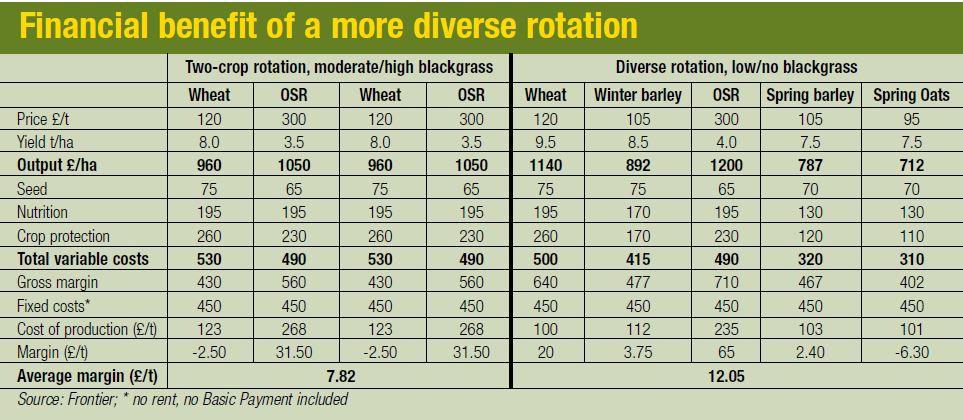

“Wheat and oilseed rape may appear to be the most profitable crops within the rotation in a blackgrass situation. But if you account for realistic yields, blackgrass and growing pest and disease pressure are having a serious impact on rotations containing just these crops (see table below).”

Financial performance

With a longer and more diverse rotation, however, many of the issues begin to be addressed, improving the financial performance of the business. “Even where grassweeds aren’t a problem, a well thought-out rotation will provide the opportunity to spread cropping and workload, repair long term soil structural damage and build organic material in the soil.

“What’s more, it will mitigate against soil pathogens such as take-all in cereals, club root and verticillium wilt in oilseed rape,” adds Stuart Hill.

To have best effect, any change in the rotation should go hand-in-hand with care for the soil, notes Frontier’s Mike Slater. “There’s no better way to see the current status of your soil than to take a spade and start digging holes,” he says.

A visual inspection is the first step of Frontier’s Soil Report service that was launched last year. “This is a detailed evaluation of your soil, carried out by a Frontier agronomist, and designed to be the basis of management decisions around achieving progressively higher crop yields,” he explains.

“Every grower has vulnerable fields, so now’s the time to identify them, assess exactly what the problems are and start to decide what to do about these.”

The Soil Report aims to quantify various parameters, to assess the physical, chemical and biological status of the soil and give an idea of its overall vitality. “There are many ways to measure a soil’s physical properties, but we focus on three: its density, porosity and compaction vulnerability. These quantify and benchmark what you should see when you dig a hole.”

Cultivations tend to burn off soil organic matter (SOM), and there’s a direct relationship between SOM and a soil’s vulnerability to compaction. “Running tyres at the wrong pressure or the wrong type of tyre is a common way to cause compaction. Grain trailers are a real culprit, and it’s good to see that many people have now switched from super singles to radial tyres and are taking steps to reduce the damage caused to soils at harvest,” notes Mike Slater.

Less understood is the impact of overall axle weight, however. “Machines are getting bigger, and while you can spread the weight with an appropriate tyre, the more weight transferred to the soil, the deeper the compaction goes.”

There’s only so much that can be done to address the problem – switching to lighter kit often isn’t practical. But it’s important to be aware of the axle weight transferred to the soil and when it can lead to compaction, he says. “Harvest is the key time – the wet conditions this year have made soils particularly vulnerable – so try to stick to tramlines, unload on headlands and use chaser bins, for example. Consider travelling with a three-quarter load, rather than filling trailers to the brim.”

Cultivation and drilling equipment can also put soils under serious pressure, continues Mike Slater. “Put a mounted power-harrow drill combination on the back of a tractor and fill the seed hopper and that’s a massive load that will be transferred through the back axle. The tractor will also be unbalanced, but evening that out will mean adding yet more weight to the unit and pressure to the soil.”

When it comes to alleviating the damage, the spade should come out again, before the subsoiler, to assess the extent of any compacted areas, notes Mike Slater. “Subsoiling can do more harm than good if it’s done wrong. Find out where the compaction lies, then set the depth to just below that layer. You’re aiming to lift the soil, but keep the structure intact – it’s a delicate balance.

“But conditions must be dry enough to fracture the soil. It may be this only happens once every ten years. So if conditions aren’t right, limit subsoiling to the tramlines and headlands only,” he advises.

To build a more resilient soil means building SOM, however. “There are two sides to this – firstly, you’re looking to build soil biology. Provide the right food stock and the bugs will come. It’s the life in your soils that holds them together – exudates from microbes form the gum that binds soil particles. And it’s the life in your soil that keeps the clods apart – worms give it its porosity and fungi its crumb structure.”

C:N ratio

It’s also important to consider the carbon/nitrogen (C:N) ratio of any amendments (applied organic matter), he continues. “The ideal range is 10:1 to 15:1. Farmyard manure generally fits that parameter. Chicken litter is about 8:1, so has plenty of readily available N.

“Straw is about 40:1, so for every tonne chopped and spread, bugs need about 4-5kg of N to process it. This should be borne in mind as it will immobilise N, particularly at establishment. However, this N is released in time, so if there’s a steady throughput of amendments, the net effect should be minimal,” he adds.

Cover crops provide the ideal form of organic matter and can also help with soil structure, notes Paul Brown of Kings. “There are two essential decisions to make with cover crops,” he says. “Firstly, decide what mix of crops you will grow, then how you will destroy it.”

Choice of crop comes largely down to what else is in the rotation. “You are adding another crop, so bear rotational issues in mind – don’t follow vetch with beans, oats with spring oats and radish may not be wise in a tight rotation with oilseed rape.”

Having said that, radish is his favoured crop to include. “In four years of trials work, it’s consistently performed best for soil structure and organic matter,” he reports. “Radish will work best in the Aug-Jan window, putting down the deepest and quickest penetrating root. About two thirds of its biomass is above ground, and the leafy material is valuable organic matter.”

Along with deep, structuring roots, aim to develop some shallow, lateral roots to build friability in the surface layer, advises Paul Brown. “A cereal or vetch will do this job, so a radish and oat mix is the bees knees of cover crops. Vetch also fixes N, and, along with phacelia, can help build mycorrhizal fungi in the soil.”

Cover crops are best drilled, but don’t need much soil preparation and can be drilled direct, he says. “Seed size varies considerably between crop types, so watch for settling within the seed hopper, and ideal depth may be a compromise – 12mm will be adequate for most crop types. Consolidation with a packer roller is important.”

Cover destruction can be anything from grazing to ploughing. “It should fit in with when and how you will establish your next crop. If spraying off with glyphosate, bear in mind the cover will take a long time to die off, so this may need to be applied before Christmas for early spring drilling,” he notes.

Arable resilience

As crop prices have fallen, while input costs have been steadily rising, on-farm profitability for UK arable farmers is being squeezed. Only the businesses that have a resilient strategy in place will weather the downturn and emerge fitter and stronger for the opportunities that lie ahead. But what does that mean on farm?

In this sponsored series, CPM has teamed up with experts from Frontier to examine the everyday management  decisions and explore what separates a resilient strategy from one that leaves a business exposed to the harsh cuts of an economic downturn. From nutrition and precision farming, through seed choice and markets to soil health and rotations, the aim is to highlight the elements that ensure the arable business thrives.

decisions and explore what separates a resilient strategy from one that leaves a business exposed to the harsh cuts of an economic downturn. From nutrition and precision farming, through seed choice and markets to soil health and rotations, the aim is to highlight the elements that ensure the arable business thrives.