A focus on cost of production helps Lincs grower Andrew Ward make informed business choices. CPM visits to find out how a partnership approach to on-farm trials feeds into this process.

Any change we make is properly costed.

By Tom Allen-Stevens

Inspecting one of Andrew Ward’s fields of wheat, it’s difficult to pick holes in it. The crop is fairly free of disease, even in growth with no visible signs of blackgrass. But this particular field has been one of the costliest to grow this year.

“It’s part of 211ha we originally cropped with oilseed rape, but 87ha, including this field, failed to establish well. So we took the decision to abandon the crop and redrill with Shabras winter wheat towards the end of Oct,” he explains.

Every cost, including spares and repairs, fuel oil and labour, is broken down and allocated to each enterprise.

“We’d already spent £237/ha growing the OSR crop, so it was a hard decision to make. But I sold the wheat forward so already know what it will return, depending on final yield. Despite the extra costs, the wheat will still bring more than I would have received from a poor OSR crop.”

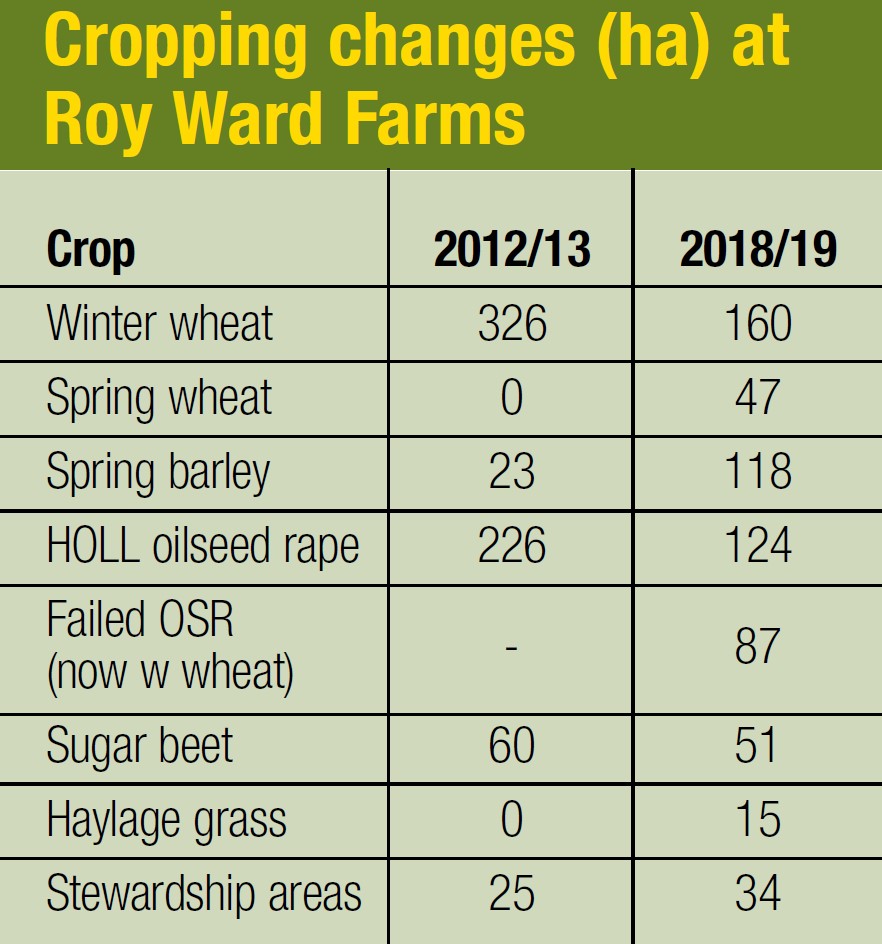

Andrew’s not shy of making decisions that involve fairly major changes to the farming system at Roy Ward Farms, near Sleaford, Lincs. Farming 650ha that vary from heavy clay to lighter heathland soils, the rotation has switched in recent years from mainly winter crops to one where spring crops now dominate.

“Every decision we take on the farm revolves around blackgrass – there’s a zero-tolerance policy. But we have to ensure farming retains it profitability. So any change we make is properly costed – it’s essential to have a clear idea of exactly what your costs are so you can gauge the overall effect of a management change on the entire business.”

His interest in costings started in the mid 1990s. “We had a steel-tracked crawler and wanted to change it to a rubber-tracked Challenger. Bill Basford from ADAS encouraged us to look at every aspect of operating a machine over a period and cost it up, including fuel that we’d never attributed before. A lot of what he said made perfect sense.”

Working with farmers like Andrew informs Matt Garnett how he can help other growers get better value from their crops.

The figures revealed the new rubber-tracked machine was going to cost slightly more to operate than the old steel-tracked crawler. “The capital cost was considerably more, but the difference in its speed and sophistication was huge – it was capable of doing a lot more, and this was reflected in the hourly costs. We looked at swapping one of the other tractors as well and realised we could actually replace three machines, including the crawler, with one,” recalls Andrew.

The exercise focused his mind on recording costs for every operation and allocating these, so that he could work out exactly how much every operation costs. This came in useful a few years later when the farm switched out of ploughing into min till. “I was offered the use of a Simba Solo over the autumn, and if I liked it, we’d buy it, but if it didn’t work out Simba said they’d take it back. It gave us the opportunity to properly cost up the operations and compare them.”

Today, every tractor carries a diary and a log is kept of every operation, with fuel and time for each operation also recorded. “We keep a close track on spares and other workshop expenses and attribute these as well,” notes Andrew.

“It’s a discipline everyone on the farm has to follow, but the information we get is well worth the hassle and there are spin-off benefits – Ian Stubbs, our main arable operator, aims to beat his own figures and often comes up with innovative ways of shaving a bit off costs.”

More recently, the focus has been on cost of production. A determination to get to grips with blackgrass has driven the cultivation policy and changes in the rotation. This has seen the spring cropped area increase and now dominate the cropping.

“There is a view that spring crops aren’t suited to heavy land, but we’ve shown they are. The key is to prepare all land in the summer to early autumn. So we don’t start to drill OSR until all the winter wheat and 75-80% of spring-cropping land is ready for drilling. If you leave cultivations in your spring-sown area until after the autumn crops are drilled up, it’s too late and the land will be too wet,” he says.

So how has the move to spring cropping helped his cost of production? “It’s easy to spend as much as £220/ha on herbicides in winter wheat – this simply isn’t sustainable. We’ve managed to achieve a decent yield in spring cereals that, along with the lower herbicide bill, has reduced our unit cost of production.”

Andrew believes that if he was still following the same cropping regime today he had before the change, his cost of production for winter wheat would probably exceed the price he could get for the crop. This is mainly due to the yield penalty from the blackgrass burden, as well as higher herbicide costs.

“The spring barley cost of production is actually £10/t higher than wheat, but the wheat crop doesn’t contribute as much to blackgrass control compared with spring barley which usually turns in a comparable profit. The biggest difference has been in not allowing any blackgrass to go to seed.”

With a high level of resistance to post-emergence chemistry, Andrew has reduced his use of herbicides and has sprayed out with glyphosate in the spring those patches that haven’t been controlled with autumn herbicide. Any remaining blackgrass is hand-rogued by a team who make up to three passes through the crop in June. “We spend as much on hand-rogueing as we used to spend on Atlantis. Now that bill is coming down from £56/ha on average in 2016 to just £21/ha last year as there’s progressively less to remove, and we haven’t had the need to spray out any patches for two years.”

Now it’s oilseed rape that’s under scrutiny. “Our cost of production has varied between £236 and £252/t since 2015, although I should think it will be considerably higher this year as a result of the failed crops. It’s also the one crop where I believe we get blackgrass seed return, although you can’t see it through the canopy.

“We’ve kept with OSR because it’s been profitable, but yields have been dropping and with this year’s CSFBs larvae problems, we’ve decided to reduce our area for 2019 plantings by around 75%.”

The aim is to grow OSR only one year in five or six and to get there, he plans to stop growing it for three years where the rotation is currently two spring barleys followed by OSR. “In its place, we’ll be growing spring oats and winter beans but we must be confident it would give us an improved profitability. The key to determining that will be to try some options, get a system that works in our field conditions, and use our knowledge of costings to refine it to ensure we end up with a more profitable rotation.”

Cropping changes (ha) at Roy Ward Farms

Partnership approach to profitable progress

You’d rarely turn up at Glebe Farm, where Roy Ward Farms is based, and find it wasn’t a hive of interesting activity. A wander into one of the fields of spring barley reveals trial plots of novel spring crops are being established. As an Agrii iFarm, Andrew Ward is hosting an open day this summer, and these alternative crops will be one of its highlights. Agrii’s Steve Corbett can be found netting up the plots to protect them from pigeon damage.

“Haricot beans, or navy beans, similar to the baked beans consumed widely, are one of the crops we’re looking at, as part of a project led by Warwick University,” he says.

“We’re also looking at two varieties of chick peas, that make hummus, one of soya, and a spring oat variety that makes a health food drink. We’re keen to identify crops that can be grown profitably in the UK with specific end markets, rather like the contract Agrii has with Budweiser for Explorer spring barley.

“From an agronomic point of view, we’re looking for spring-sown crops with potential to replace an OSR crop in the rotation, so a late-drilled, 90-day crop, preferably with white straw, is ideal. We’re also looking at barley and rye taken as forage for anaerobic digesters.”

Andrew’s keen to understand more about novel crops. “The benefit we get from these trials is an idea of how the crops perform under our field conditions, and crucially we’ll get some clear figures on costs. Within two years, I’d like to look at introducing a larger area of a crop that’s looks to be a winner,” he says.