The monsoon this autumn has dictated an unplanned swing towards spring cropping as ground conditions prevent drilling. CPM looks at some of the options growers may have for their unplanted land.

We reckon only 25% of the wheat area has been planted.

By Lucy de la Pasture

It’s been an autumnus horribilis for many, with a stubbornly positioned jet stream funnelling in low pressure systems one after the other. It’s barely stopped raining since the end of Sept and the continuous wet weather has hit wheat drilling hard.

According to AHDB’s Early Bird Survey, as a result of the weather UK growers now intend to plant 1.65 million hectares of wheat compared to 1.82M last year. The reality of ground conditions in the areas of the country most delayed means it may yet prove to be an optimistic estimate unless things improve dramatically in coming weeks, says Agrii’s head of agronomy, Colin Lloyd.

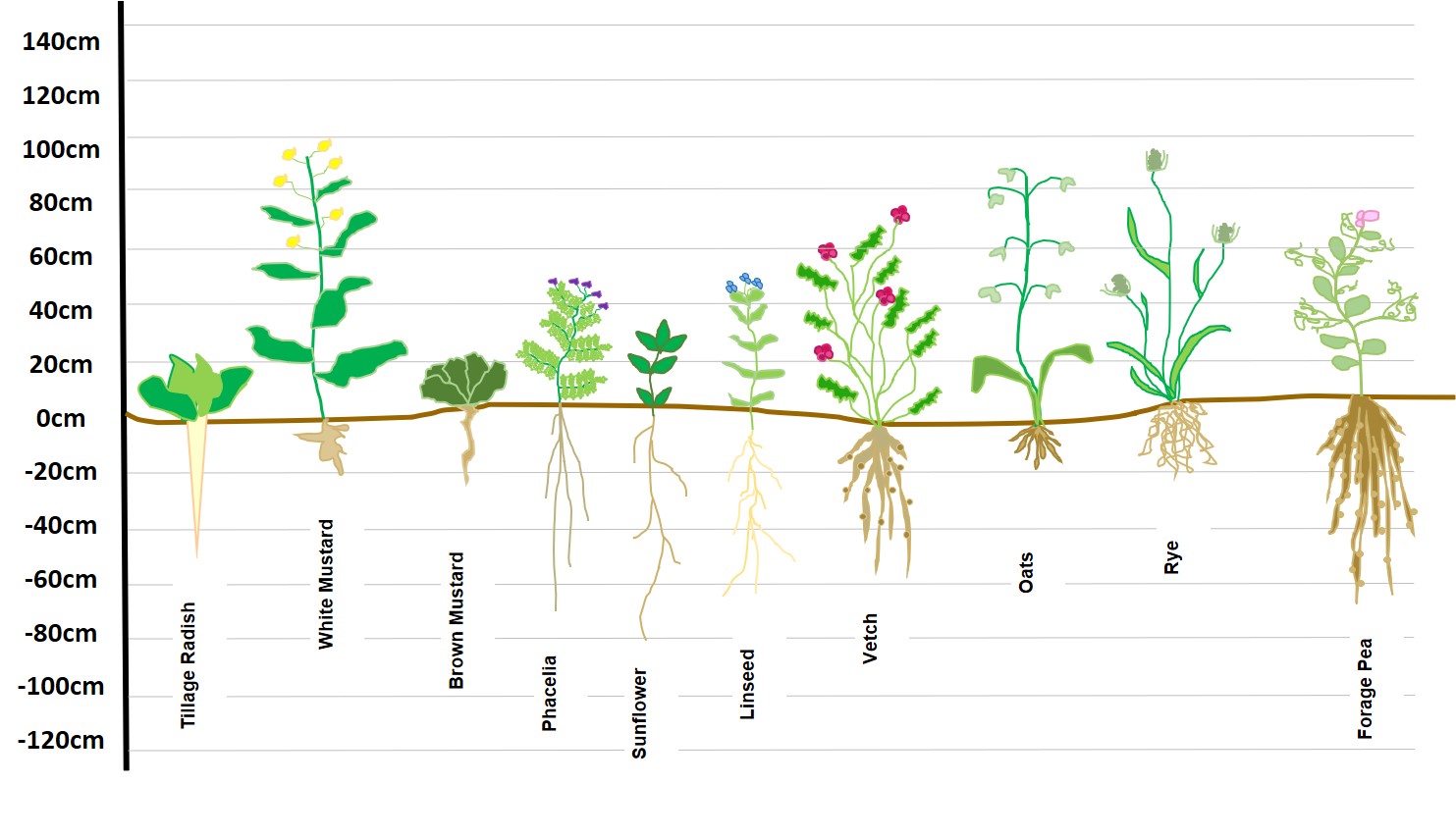

Cover crop mixes should include at least three different species to utilise their different root structures.

“In a recent straw poll of agronomists from around the UK, the amount of cereals drilled is hugely variable. Scotland managed to get winter crops in, parts of Essex have 70% in the ground but moving inland the situation isn’t as good –parts of Cambs/Lincs for example have an awful lot left to do. Nationally we reckon only 25% of the wheat area has been planted (end of Nov),” he says.

Mob grazing cover crops that will remain in the ground over the summer will stop plants going to seed.

Looking at the data from Agrii meteorological stations across the country, it’s easy to see why drills are laying idle. At the Agrii trials site at Stow Longa in Cambs, there’s been 130mm of rain since the last week of Sept – that’s been enough to make drilling difficult, says Colin.

“Further north in Lincs there’s been 300mm and in Yorks, 400mm of rain. Moving west to Glos, the rainfall adds up to 330mm. These are hugely significant levels over a couple of months,” he says.

“While there’s a prospect of still getting some winter wheat in before the end of Jan on some fields, the time for winter barley has already passed because yields would take a big dip if planted now,” says Colin. “KWS Firefly, KWS Zyatt, Dunston and LG Spotlight can be drilled up until mid-Feb, with Skyfall to the end of Feb.

“Winter beans can also go in late. In Agrii trials we’ve found winter beans planted at the end of Feb yielded as well as the best of the spring beans. Is it the usual thing to do? No, but then it isn’t a normal season,” he says.

“Winter oats are often drilled in the spring in Scotland when the weather goes against them and this is another option for growers because the crop will do well enough, but there might be a slight loss in grain quality and of course they’ll mature later.”

Colin says that many growers are now putting the frustration of the autumn behind them and looking at a plan B, which generally means more spring crops.

“The most popular option is likely to be spring barley but for those that don’t have seed ordered already, it’s going to be a case of what’s available rather than which variety. Spring beans have already sold out. Spring oilseed rape would be my least preferred option because of pest problems with both cabbage stem flea beetle and pollen beetle to consider,” he says.

“Linseed is another option to consider, but you have to consider that diquat has gone so it will need to be a kind Sept for harvesting”

Where growers have spring barley in the grain store, home-saving some seed may be a good idea, he adds. “Needs must if there’s not enough certified seed to go around, but it’s important to send some into the seed lab and get it tested. Applying a single purpose seed dressing is also essential, with the addition of manganese to aid establishment worth considering, so consider a mobile seed cleaner.

“Planting home-saved seed without testing or treating just adds another layer of risk to growing the crop,” he says.

Farmacy agronomist Alice Cannon says her growers in North Lincs currently have around 10% of winter wheat in the ground and on some farms winter beans have already been planted in place of winter barley.

Alice points out that with so many autumn crops not in the ground, there will be a significant knock-on effect – with any crops still to go in likely to be later to harvest, beginning a late cycle which will affect the following crop. Consequently she believes it’s a good idea for growers to have an eye on autumn 2020 when making decisions for this spring.

Both agronomists say patience will be a virtue well worth having when the ground eventually begins to dry out. Getting itchy feet and muddling crops in is the worst thing that could happen, with consequences that will be seen in the next year’s crop and possibly further into the rotation.

Alice says soils are fragile after all the rain, with some slumping and silt washing through the profile. “It’s going to be important not to force things which will just compound any problems with the soil. The best time to assess soils is when they start to dry out, usually in Feb, and go and inspect with a spade to figure out the best plan of action. Some soils will have compaction at depth, which may need metal to lift it but at the correct depth.”

Colin agrees a spade will be an essential tool and will show where water is trapped in the soil profile, even in a min-till situation.

Cover crops could play an important role where soils need a helping hand to restructure. Where potatoes, onions or sugar beet crops have been harvested in difficult conditions, there’s likely to be a range of soil damage and for the very worst of these it may be prudent to consider taking the land out of production and focusing on repairing it for next autumn, believes Colin.

“You need to get the soil back into reasonable condition to grow a decent crop. In most cases if you know where the soil is at then it’s possible to rectify it but, in some cases, it may be best to look towards a successful autumn drilling in 2020. It may just be a tiny percentage of the farm, field specific or may be more widespread.”

Alice is in agreement with Colin about the longer-term effects of damaging soil structure. “The effects can often be seen in following crops for a couple of years but on heavy land which has been badly mauled, it may take 5-8 years before it recovers with major yield penalties for the following crops.

“Some of the environmental mixes will still offer financial benefits, as well as environmental ones – encouraging predators and making it easier to farm in a sustainable way. A longer-term cover crop is another option, such as oats/clover/linseed mix or radish and phacelia may be helpful here too.

“It would enable early entry in autumn 2020, having done its job pumping water out of the soil and making it more friable. It can also be a good way of managing soil moisture before planting OSR or winter barley,” she says.

Alice highlights that if a cover crop is going to be in the ground throughout the summer then it’s best not to allow it to go to seed, either topping or grazing to prevent unwanted seed return. She warns against using a mix with phacelia because volunteers can be problematic if the parent is allowed to go to seed.

“If you’re grazing with sheep then mob graze, where sheep are stocked at high density for a short period of time to take the cover crop down to about 2.5cm and then the stock are moved to allow regrowth. This method gives a more even graze and distribution of manure/nutrients.”

In situations where fields haven’t been planted or have failed, Alice suggests leaving any volunteers that are currently providing ground cover. “Prioritise any brown fields to get a crop in and don’t worry about spraying off volunteers now until before drilling. Most drills can cope with a little bit of biomass and the volunteers are now acting as a water pump, so will help with an earlier entry in the spring.

“The same applies where an OSR crop has failed and leaving what’s left of the crop means the soil will be in a better condition when replanted,” she says.

Colin suggests growers prioritise the order of planting where different spring cereals are planned. “Spring wheat should be the first to drill and then either spring barley or spring oats, which is the most aggressive and will ‘go for glory’, so it won’t matter if they’re last to be drilled. If spring wheat is planted late then the incidence of gout fly damage and ergot will increase,” he explains.

In Agrii trials at Stow Longa last year, spring barley planted on 20 Feb, which was a very kind month, performed less well than crop planted a month later. “The yield penalty for drilling early on heavier land was 1.5t/ha where ground was ploughed and over 2.0t/ha after a cover crop or a deep cultivation system was adopted. The key is to drill in a drying seedbed with increasing soil temperatures to get the crop in and out of the ground as quickly as possible.

“Even more patience is going to be needed when it begins to dry up in 2020. The success of spring barley to compete with blackgrass is purely down to percentage establishment, so you could be defeating the very reason you’re growing it by going to early.

“But what we have seen over the last six years of extensive study, is that if you get this right there are some very useful gross margins earned, so certainly all is not lost and plenty to gain,” he concludes.