Peas are a notoriously difficult crop to grow, but experience through YEN suggests they can shine a light on limitations across the rotation. CPM visits an Oxon grower who’s looking to gain an insight.

The crop’s sometimes referred to as the canary down the mine.

By Tom Allen-Stevens

There’s something to be said for the satisfaction you get from a well established, even pea crop – one that’s set its stride and appears to have everything it needs to fulfil its potential.

That’s probably why David Passmore is only too pleased to bring you to his crop, that sits like a thick, sprung mattress across his shallow soils, lying over chalk near Wallingford, Oxon. “Peas are a crop you either love or hate,” he says.

Get a pea crop right and it can be immensely rewarding.

“They’re probably not for the huge farming enterprises with just one combine, that need crops to fit their system. But if you’re someone who celebrates that they’ve drilled or harvested on the right day, it’s a crop that can be immensely rewarding.”

For David, for whom peas have been part of the rotation for the past ten years, those are the two days that matter in the life of the crop. “They’re a good crop to have on the farm and get you away from a winter rotation. Some of our best yields have followed a pea crop,” he says.

If you get them wrong the crop will punish you, though, which is why he believes there’s so much to be learned by getting it right. “The trouble with peas is the huge variability of yield. Our average is 4.5t/ha and our best is 5.7t/ha. But last year we achieved just 3.4t/ha.”

With 300ha of cropped land, Passmore Brothers specialises in seed crops. There are 12ha of Mankato peas – a pre-basic to basic crop grown for KWS. A similar area of Campus winter oilseed rape, grown for seed, is carefully rotated around the farm, with 100ha of winter wheat (KWS Crispin, Kerrin and Firefly) and 50ha of KWS Sassy and Irina spring barley.

But an important ‘crop’ for David is his livestock – the spring barley’s undersown with grass that’s grazed for two to three years with 160 head of Limousin beef cattle and 200 breeding ewes, before returning to a wheat crop. “On our lighter soils, we put forage rape into the ryegrass after its cut of silage, then back into spring barley, achieving three crops in two years.”

David credits the livestock in the rotation for his very low level of grassweeds. “There’s no blackgrass on the farm and this is something we’re meticulous about – we’ll always rogue any plants we see and in my farming career I’ve only ever used two cans of Atlantis (iodosulfuron+ mesosulfuron).”

His rotation, with its inherent focus on soil health, brings him some impressive yields – an ardent member of the Yield Enhancement Network (YEN), his wheat came fourth last year with a 14.01t/ha crop of KWS Kerrin. This year, he’s also joined the pea YEN, but that’s not about the competition, he says.

“What I like about YEN is being involved – what you gain from it is what you put into it. So the pea YEN is less about the competition and more a learning exercise.

“The theory of growing peas is really very simple – the day you plant it has its maximum potential yield, so everything you do after that is aimed at retaining that potential. YEN helps you break it down so you can focus on what’s important. The first thing it teaches you is that you only see half your crop – the rest is underground, but that’s almost the most important part.”

The fortunes of the pea crop itself are largely determined at drilling. The roots are incredibly sensitive to compaction, and David takes great care to preserve the soil structure. “Peas are the most critical crop we grow for planting conditions, and you can’t go by calendar date. 90% of its yield potential is determined on the day you plant.”

Preparations for this start the previous autumn. Land is generally turned with a 5f Kverneland plough in Oct or Nov and left over winter. “You can min till other crops, but the old adage ‘you have to plough for peas’ still holds true, and while we do have catch and cover crops that we graze with sheep, not before peas.”

The aim is to prepare the ground in winter, including perhaps a pass with a 4m Flexi-Coil, so the 4.8m Kverneland tine seeder drill can go straight in when conditions are right. That was 28 March this year, although David had to wait until 20 April last year.

As in the wheat YEN, the key to a high-yielding pea crop is to maximise crop cover. “Biomass drives yield, and there’s no correlation with thousand grain weight – it’s down to seeds/m². The theoretical yield potential is 11-12t/ha, and while I know I’ll never get anywhere near double figures I’m intrigued to know where I’m going wrong.”

This theoretical yield is broken down to peas per pod, pods per plant and plants/m² and David’s been following the protocol to see how he can lift crop prospects at every growth stage.

That starts with seed rate. “We’ve raised the seed rate on the back of YEN – it used to be 80 seeds/m² but now we drill at 100 seeds/m².”

Nutrition is of vital importance to a high-performing pea crop. “We haven’t applied any P and K recently because our levels are good, although I am considering some Polysulphate next year. One aspect we have taken advantage of, though, is the tissue testing service through YEN.”

Two leaf samples are taken for analysis – one at second node, just before flowering and the other just after flowering. “The analysis showed up a lack of boron, so we applied this with magnesium in May. We’ve also applied Photrel Pro, which is a combination of micronutrients,” says David.

“YEN is showing us that, while the return you get from one micronutrient application may be insignificant, making many little steps builds crop momentum and delivers a significant yield benefit overall.” Marsh spot is also a concern, with a dose of manganese applied at the end of April, followed up with a second in June.

Disease pressure varies considerably year-to-year. “Last year, we got away with a dose of Alto Elite (chlorothalonil+ cyproconazole). But this year, botrytis is what worries me, with the damp weather during flowering, so we’ve applied Amistar (azoxystrobin).”

David’s more reluctant to apply insecticides however. “Pea moth is the main concern. We’ve had traps out and haven’t reached threshold levels. I have seen aphids in the crop, which is a worry, but I’m holding back from spraying to allow beneficial numbers to build. It also helps in the following wheat crop if you’ve used less insecticides.

“You have to be on the ball with peas, though. It’s a crop that moves fast, so you make one fungicide application, for example, and find it needs another in as little as two weeks.”

Timeliness is absolutely critical when it comes to harvest, he says. “You have to put the combine through the day they come right, which for peas is below 18% moisture. The key aspect with blue peas if you want the premium is to retain the colour. If they stay out in the field, this bleaches the peas. Harvest is the second of the key days in a pea crop’s life.”

Another reason to harvest when the time’s right is to catch the crop when it’s standing. Much of this is down to variety, says David, and Mankato is one that he’s found stands well. While the combine will fly through a standing crop, it can take many times longer to pick one up off the floor.

Once the crop is harvested they’re put on a drying floor with ambient air blown through until the crop reaches around 14% moisture. “They need to be stored in the dark, but are relatively easy to dry,” he says.

After last year’s disappointing yield, David’s current crop looks set for a good result. What’s more he’s hoping the extra attention he’s given it throughout the growing season as a result of YEN will also pay dividends. If not, at the very least he will be able to benchmark his performance against others to see where improvements can be made.

But perhaps it’s the value over the rotation where the crop delivers the most. “Over a farming lifetime, you learn which are the right things to do,” he says. “That’s where peas fit in – they’re good for the farm.”

Monitoring sheds light on key factors for peas

There’s more information on the pea YEN protocol and how to get involved in the new bean YEN, which has similar objectives, in the current issue of The Pulse Magazine, that accompanies the July issue of CPM. There’s more detailed technical information for growers, while the PGRO website and new app have Peas are the crop that can tell you more about the health of your soils that perhaps you want to know, suggests independent consultant Keith Costello. “The crop’s sometimes referred to as the canary down the mine. Some crops will tolerate a certain amount of extremities, peas will not. You have to think ahead to give them the best chance and the attention they deserve when it’s needed.”

Keith’s been helping PGRO and ADAS set up the pea YEN and adapt the basic principles of YEN to the crop. There’s a core group of growers whose crops he’s visited each year to make regular inspections. That’s now developed into a protocol, and farmers have been invited from further afield to take part, with the aim of improving yields.

“The average yield for dried peas rose steadily from the 1980s at around 3t/ha to a peak at the turn of the century of about 4t/ha. But since then, it’s settled back down to close to 3t/ha. So why is that? My aim is to help growers identify the key factors and bring yields back up again,” he says.

The maths is fairly simple: a healthy pea plant will usually grow four pairs of pods per plant, with seven peas per pod. “That should bring 50-55 peas per plant, but typically you get a third of that, hence why we’re averaging a third of the crop’s potential yield. If you understand what’s going on in the plant and why it decides to set a lower number of peas, you can identify ways to increase this,” he reasons.

So as well as monitoring crops for their establishment, pod and pea set, Keith’s been assessing what key factors set these critical contributors to yield to help growers monitor and benchmark their own performance. He’s concluded there are five:

- Establishment – This is absolutely critical, says Keith. Conditions have been kind this year, with dry soils allowed to self-structure and fieldwork completed without damaging their integrity. But that wasn’t the case last year, so a keen focus on maintaining structure will make all the difference at establishment.

- Roots – Keith’s observation is the rhizosphere below a pea crop today is not as fibrous as it once was. He speculates this may be down to heavier machines bringing more compaction to soils with lower organic matter content, restricting the sensitive roots. But very little research has been carried out in this area, so more work is needed to understand the rhizosphere.

- Viruses – the incidence of some of the common pea viruses, such as pea initiation mosaic virus, and the prevalence of its aphid vectors has increased, Keith believes. A badly affected plant will produce significantly fewer peas, sometimes into single figures. Rather than straight treatment, he’d like to see more growers adopt an effective integrated pest management strategy across the rotation.

- Nutrition – Sampling across crops at different growth stages is highlighting a surprisingly high number of incidences where crops are low or very low in certain nutrients. What’s less clear is whether these apparent deficiencies are relevant and at what stage they limit the performance. The first step for growers is to carry out leaf tissue analysis to put themselves in the picture.

- Knowledge exchange – passing on experience and advice within the business and from farmer to farmer is key with a crop like peas, that may drop in and out of the rotation and is a somewhat specialist crop. This is particularly important in large farming businesses where farm managers retire or move on, without the succession of knowledge that may happen more naturally within a family business, Keith suggests.

He recommends two routes for growers to get more out of their pea crop. “Firstly take advantage of the technical information on offer from PGRO. Once you look in detail at your crop, you can identify the technical aspects to address, and the information is available to inform this.

“Secondly, share ideas. Increasingly within YEN it’s this two-way exchange of knowledge that is helping those growers who are involved make better decisions going forward. That’s even more important in peas where we have less of the specialist knowledge that perhaps we once had.”

And for those who have given them the attention they deserve, Keith believes the prospects this year are good. “When peas perform, they’re a marvellous crop, and there’s every chance that most growers will enjoy that satisfaction this year. So fingers crossed.”

- updates on key diseases and pests, such as pea moth.

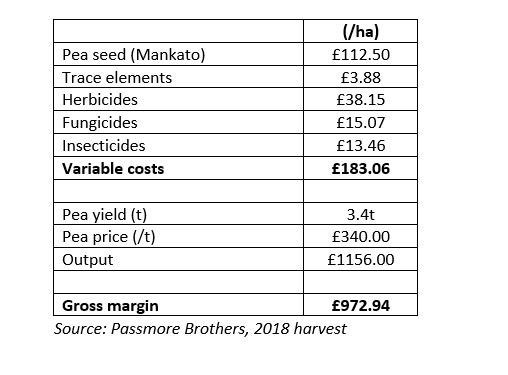

Passmore Brothers large blue peas: how the finances stack up