Climate change is set to move up the agenda following the release of a number of reports that position how UK Farming fares. Introducing a major new editorial initiative, CPM assesses what it means for the arable sector.

UK Agriculture is in a good place to lead global efforts to drive down emissions.

By Tom Allen-Stevens, Charlotte Cunningham and Lucy de la Pasture

Climate change champion or carbon culprit? Among the virtue signalling, bold ambitions and doom-ridden projections on global warming, whether farming and individual farmers are fuelling the problem or providing the solution may lie at the heart of what’s described as “the single biggest issue facing humanity”.

This month, the NFU publishes a report set to put flesh on the bones of the ambition its president Minette Batters set out in Jan to reduce net agricultural emissions to zero by 2040. A similar target (net zero by 2050) was announced for the UK as a whole by former Prime Minister Theresa May. This followed recommendations made by the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) that advises the UK government on emissions targets.

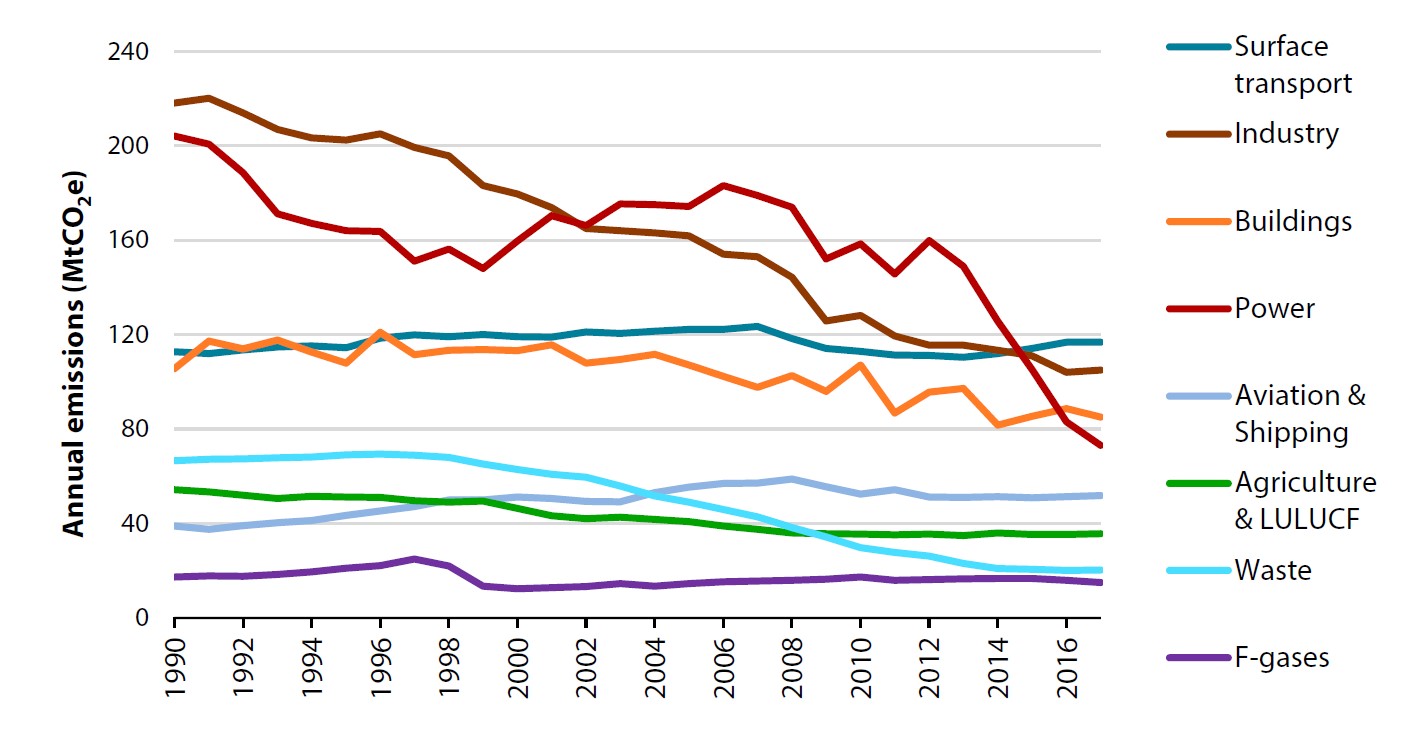

UK greenhouse gas emissions

Source: BEIS (2019) Final UK greenhouse gas emissions national statistics 1990-2017; CCC analysis. LULUCF = land use, land use change and forestry.

Prompting the parliamentary position has been a palpable rise in public interest, from the civil unrest unleashed by Extinction Rebellion to the crusade by Swedish schoolgirl Greta Thunberg to avert what she sees as an “existential crisis”. MPs on all sides of the House of Commons have been quick to recognise the voting value of signalling support for such virtuous ventures at a time when some polls suggest Britons are rapidly losing faith in their elected representatives.

So just what is the role for the UK arable farmer in this noble crusade, and what will be the reward for those who embark on it? It’s those two crucial questions CPM has set out to answer in a major new editorial initiative. The journey starts here, while we also address what it means for the kit on your farm and the implications in particular for root-crop growers.

It was last month’s report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) that put agriculture’s role squarely into perspective: “Agriculture, forestry and other types of land use account for 23% of human greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions,” said Jim Skea, co-chair of one of the IPCC working groups looking specifically at land use.

“At the same time natural land processes absorb carbon dioxide (CO₂) equivalent to almost a third of CO₂ emissions from fossil fuels and industry.”

Food sits at the centre of the issue, with climate change affecting all four pillars of food security, notes the report. But while the CCC in the UK recommends dietary changes away from meat and dairy as part of the solution, that’s not what IPCC put forward, contrary to media reporting at the time it released its findings:

“Balanced diets featuring plant-based foods, such as coarse grains, legumes, fruits and vegetables, and animal-sourced food produced sustainably in low GHG emission systems, present major opportunities for adaptation to and limiting climate change,” said Debra Roberts, co-chair of another IPCC working group.

Land must remain productive to maintain food security, says the report, and this puts limits on its potential to reduce other emissions sources, such as from transport and energy use, while it also takes time for trees and soils to store carbon effectively. But the IPCC believes “desirable outcomes” that will reduce and, in some cases, reverse the adverse impacts of climate change will come from “locally appropriate” policies and governance systems.

“Land already in use could feed the world in a changing climate and provide biomass for renewable energy,” said co-chair Hans-Otto Pörtner. “But early, far-reaching action across several areas is required. Also for the conservation and restoration of ecosystems and biodiversity.”

Fertiliser is lightening its carbon footprint

Net Zero can only be delivered by solid government policy commitment, believes NFU combinable crops chairman Tom Bradshaw, but a crucial first step for industry and individual farmers will be to know where they currently stand. “The first and arguably most important job, is to present the industry as part of the solution and not the problem. This opens doors for investment, but we need robust and relevant data to give us a baseline and targets,” he says.

There’s one point on which he’s adamant, however – the NFU is not going to accept policy changes that simply encourage arable reversion and land put into forestry as the only solutions. “Scaling back production here simply exports our food requirement and carbon emissions, out of sight and control of the UK,” he points out.

“For Net Zero to have political longevity there must be support in place. Whether this is market driven or from the government, policy has to provide the solution for more a sustainable future without compromising quality of life for consumers and without making them – nor farmers – worse off,” says Tom.

These have formed the overall objectives for the NFU as it’s fleshed out its Net Zero proposals, says Dr Jonathan Scurlock, chief adviser on renewable energy and climate change. “UK Agriculture is in a good place to lead global efforts to drive down emissions, and there’s great potential for the arable sector, particularly in enhancing on-farm soil carbon storage and displacing fossil fuel usage.”

Jonathan believes the more progressive grower already has a good grip on financial cost per tonne and knows how to influence this to improve productivity. “So the move for these farmers to think in terms of carbon cost per tonne is a relatively simple one. Typically it involves precision-applied inputs and IPM, so less input for the same or more output. Some have also found cost savings through moving from conventional tillage to min till, or to controlled traffic systems, and this will have an associated carbon saving, although there’s no one-size-fits-all system.”

Novel ideas lead a wind of change for seeds.

It’s a shift from pure production to productivity, he continues. “There’s no point producing a 12t/ha crop with a massive carbon footprint. Equally if you implement measures that lower your crop yield without a proportionate lowering of the carbon cost, there’s no net saving. That’s why thinking in terms of cost per tonne is particularly useful.”

Jonathan sees a number of options to improve the storage of carbon on farmland, whether this is in soil, hedges, trees or farm woodlands. “Farmers are identifying less productive field corners and areas of land for alternative uses, but they need a fair reward for such changes. This should reflect the risk and commitment, as well as the capital cost employed, of turning land over to woody biomass or shelter belts for example.

“But we’re not going to deliver our aspiration only through productivity improvements and carbon storage. The lion’s share will come through opportunities in the bio-based economy. Active GHG removal inevitably relies on photosynthesis. The more we can develop a supply chain that captures CO₂ and uses it as a feedstock for society’s needs, the faster we can drive down emissions.”

The quick wins will come from measures such as E10 – a proposal for a government-decreed mandate of 10% inclusion of bioethanol in petrol. This, says the NFU, would be equivalent to taking 700,000 cars off the road and put purpose into the multi-million pound ethanol plant in Hull which is currently mothballed.

“This is an area where the industry must work together, and also with other stakeholders, such as the Green Alliance, Sustainable Food Trust and World Wide Fund for Nature, and make the case to the Treasury for what farmers and land users can achieve. But some groups blow hot and cold on bioenergy, so we must be clear on the benefits and ensure these are robust.”

Longer-term solutions lie in novel materials, produced from arable crops, in which carbon is captured and may displace materials sourced directly from fossil fuels or currently requiring energy-intensive manufacture. “The potential big wins are in alternative crops that also open up the rotation and are agronomically beneficial – hemp is an excellent source of fibre and fantastic for smothering weeds, for example, but currently requires a Home Office licence to grow it.”

Soil presents a big unknown, Jonathan points out. “We believe there’s potential for enhancing on-farm carbon storage and capture through different approaches to soil and crop management, and we’re keen for this to become a core feature of the new Environmental Land Management (ELM) contracts. But it’s tricky, because we don’t know enough about how much carbon you can sequester, let alone what techniques work best, to inform how this is rewarded.”

One suggestion is to have a network of arable units, such as the AHDB Monitor Farms, where various cropping and cultivation methods that attract an ELM are put to the test and closely monitored for net emissions. They would then act as proxy farms, so ELM payments to other scheme participants would be based on actual results from the monitor farms.

“We’d have to be careful not to put all our eggs in one basket, be open-minded and flexible. So farmers would be encouraged to take on a portfolio of measures that are periodically assessed and then payments adjusted to take account of those that bring the most benefit,” he notes.

Whether such a plan is put into action on AHDB Monitor Farms would be very much decided by the farmers themselves, notes head of arable knowledge exchange Tim Isaac. “The activities undertaken by Monitor Farms are farmer-led, and we consult with levy payers on where resources are focused, while farmers are involved at a board level in decisions made on all AHDB’s activities,” he says.

“This form of proxy monitoring hasn’t been discussed, but that’s not to say that Monitor Farms aren’t well placed to do it, nor that much of the activity currently undertaken isn’t very much in line with the sort of carbon-capture schemes that have so far been proposed.”

One network of farms well experienced in monitoring environmental impact are LEAF (Linking Environment And Farming) members. Those certified under LEAF Marque complete its annual Sustainable Farming Review which records the integrated farm management (IFM) techniques carried out across the business.

It identifies areas where performance is particularly good as well as those where there’s space for continual improvement, says IFM manager at LEAF Alice Midmer. “The review gives farmers the chance to fully evaluate their practices, potential and contribution to sustainable agriculture. It offers a complete farm health-check allowing farmers to make more informed decisions that will drive their businesses forward.”

While the review provides pointers for improvement, it doesn’t in itself benchmark or quantify a business’ net contribution to GHG emissions, Alice acknowledges. “A collaboration between AHDB and LEAF is aiming to bring more clarity here, however,” she notes.

“There are 20 LEAF Demonstration farmers who are using the review in conjunction with AHDB’s Farmbench tool to analyse the economic impact of some of the practices they’ve adopted. It’s allowed us to start investigating how a strip-till system performs when compared with others, for example.”

Energy usage across the business is an area LEAF Marque members are encouraged to measure and monitor as this often brings both financial and carbon cost savings, she says, and an energy monitoring spreadsheet enables this. This calculates the CO₂ emissions associated with energy use, although still falls short of a full carbon-footprinting tool.

“We do advise members to use one of the tools available in addition to completing their review, although it’s not necessary for LEAF Marque status. We’ve heard good things about the Farm Carbon Cutting Toolkit (FCCT). There’s also the Cool Farm Tool while the Alltech E-CO₂ tools are geared towards livestock producers. But the challenge with all of these tools once you’ve taken the time to assess your carbon footprint, is what to do with all the data. Farmers then need practical solutions to reduce emissions and to commit to continual monitoring.”

FCCT’s Becky Willson notes the tool is “unashamedly” in-depth. It’s been developed “by farmers for farmers”, currently used by around 200 farms regularly and another 1000 sporadically, aiming at an “open and honest” approach to measuring emissions, she says. Although comprehensive, she’s found it can identify big wins where carbon savings can easily be made. An example for arable farmers here is how fertiliser interacts with the soil and the nitrous oxide emissions that result, which in GHG terms are 298 times more potent than CO₂.

“Our tool differs from others in that it takes account of soil carbon sequestration – we are currently working on a project with 75 farmers measuring what’s possible. The main aspect about measuring carbon is that areas where you make savings are usually where you can also save money. But if government policy is going to change to incentivise carbon-saving measures, the first step for any business is to assess where it stands today. This helps you understand both the potential for reducing emissions and the opportunities for sequestration.”

Farming’s roadmap to Net Zero

Net Zero is achieved when the sources of anthropogenic (resulting from human activity) emissions match the measures put in place by industry and individuals as a carbon sink. Nature currently responds to human-induced environmental change by absorbing carbon to the tune of around 11.2 Gt CO₂e/yr (gigatonnes of CO₂ equivalence per year), roughly equal to the global net carbon footprint of agriculture, forestry and other land use, according to IPCC figures.

While you could argue that already puts land use at net zero on a global scale, the quest to reduce global warming relies on reducing the current net impact of all human activity. This comes from both reducing actual emissions and applying processes that make use of and increase nature’s ability to act as a carbon sink. This, argues IPCC, puts land users in a pivotal position to help society achieve Net Zero.

In the UK, emissions from agriculture are around 46 Mt CO₂e/yr, according to government statistics. The Net Zero roadmap proposed by the NFU has three cornerstones:

Productivity

For arable producers, nitrogen fertiliser is a significant part of a crop’s footprint which is why nutrient planning and precision application and legumes in the rotation are valuable tools in a farmer’s GHG management toolbox. The NFU believes productivity improvements across all sectors could deliver around a quarter of the net savings.

Farmland carbon storage (Nature-based climate solutions)

This is the carbon-capture opportunities on farmland, such as storing carbon in soils, creating woodlands and wetlands, trees and shelter belts utilising less-productive land. This can deliver another quarter of the savings, but changes must be research driven, says NFU.

Moving to a bio-based economy

This is a major opportunity for the combinable crops sector and where NFU believes around half of the net reduction will be sourced. In the short term it’s about displacing fossil-based energy sources with bio-based, such as bioethanol and anaerobic digestion. Longer-term opportunities lie in plant-derived biomass for new composite materials, such as using straw to make building materials and natural fibres to replace plastics and synthetics. This captures and stores the carbon for the long term in society’s fabric and infrastructure, rather than using fossil fuel-based materials.