By Martin Lines

Sitting in my office writing this in 30-degree heat, I find myself doing what farmers do best: bemoaning the weather. But with recent temperatures soaring to an unprecedented 40 degrees, it has given many of us little else to think about. With the forecast for the next few weeks showing no rain and more heat for a tinder-dry landscape, it leaves scant opportunity for a reprieve from the worry. The sad reality is that weather like this will become commonplace in the summers to come.

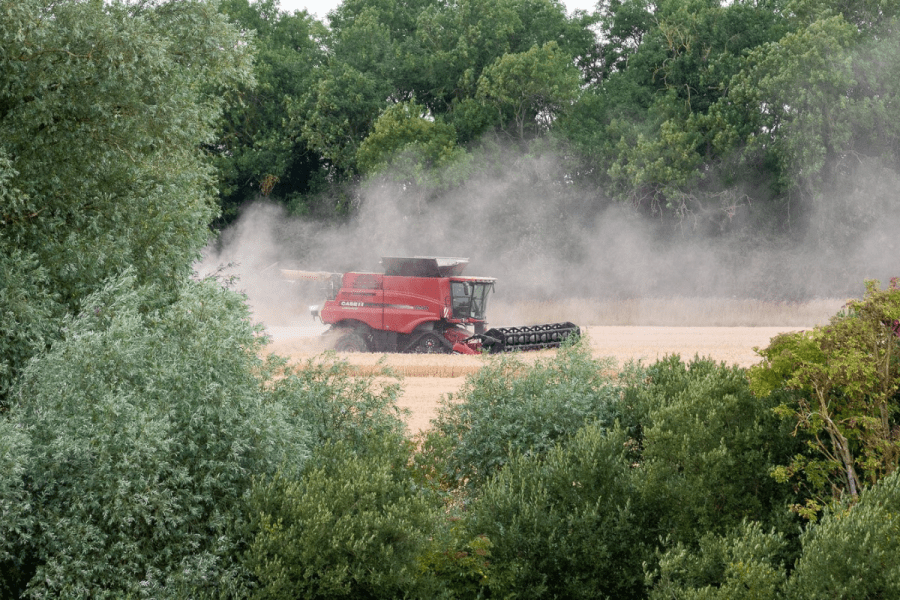

This dry heat, like a hairdryer on hot blast, has brought widespread pressure to farming. As the weather becomes too hot to handle, our crops face endless struggles. Our spring beans and barley have seen little rain since planting in March. The wild bird seed mixes we planted across the farm are struggling to grow with a lack of moisture. Word of drought is on the horizon, and so too is the possibility of hosepipe bans and restrictions on irrigation. Without water, our harvests face the risk of failure. The wildlife our farm supports will encounter the colder months ahead with diminished feed sources. Climate change is here, and its impacts are being felt the length and breadth of the landscape.

With constant reports of fires breaking out on farms around us, the importance of our water resources becomes ever more present in a country where we often take it for granted. The availability of water for irrigating crops is becoming progressively difficult. We need to look at how we can store more water when we have a surplus and build on-farm water storage to cope with the challenges ahead, including farmland ponds that are becoming vital for both the fire service and wildlife.

After a year of global weather challenges and geopolitical conflicts knocking the stability of supply chains into question, what food we produce and how we get it onto people’s plates is pivotal to future security.

It’s a time to rethink our food production locally, nationally and globally. The Nature Friendly Farming Network (NFFN) recently released a report looking at the food we produce, how much we waste, and the amount of productive land used to produce commodities not for people’s consumption.

With ever-increasing areas of land being used for energy and building infrastructure, food production from a farmed landscape has the opportunity to deliver multiple outputs that other landscapes can’t. Yet many in government are happy to turn a blind eye to the impacts of global production in the trade deals they strike with other countries. There is an unmissable opportunity for the UK to become a global leader in nature-friendly food through international trade that delivers solutions for nature, climate and food security. But first, we need the government to urgently develop a land use strategy that links up net zero, biodiversity recovery and agriculture. They need to bite the bullet of what a changing climate means and turn political rhetoric into hard action.

As hotter days become normality, I’m looking at my crops with the heat and drought in mind. This means more changes to our rotation and working out what break crops we can grow alongside the beans we’ve been adding over the past few years. I was hoping to plant more oilseed rape, but the weather forecast makes this less of a good idea. With our soils so dry, the opportunity to plant a cover crop is limited, but we will still plant one where we have spring crops planned and hope for more moisture in the air when the time comes. Each seed mix used depends on the date or month we plant it, and I firmly believe that cover crop mixes should be flexible in adjusting to changes in the weather. Don’t be fooled by the many great salespeople who are skilled in knowing the trick of a good trade but know little about the when, where and how of fitting a cover crop into your rotation.

As more farmers are looking at reducing cultivations and adding cover crops to reduce costs, the trick comes in weighing the cost benefits versus the opportunities. Speeding infiltration of excess surface water, reducing fertiliser costs and increasing the soil’s organic matter is a long game. Every seed can enhance nutrient cycling when water is in short supply. An excellent tip is that a mix of three to four plant types gives 50% more yield than a monoculture.

I’m always keen to hear from other farmers trialling seed mixes to varying degrees of success. One person’s hard learning is another person’s good advice. Do reach out – martin.lines@nffn.org.uk. In the meantime, you can find me doing a rain dance somewhere out in Cambridgeshire. At this point, it’s all we can do.

This article was taken from the latest issue of CPM. For more articles like this, subscribe here.