Britain’s largest farmer-owned grain storage co-operative Camgrain has completed an internal review and picked up an industry award for its efforts. CPM visits to assess the benefits it claims to bring to its members.

We have the facilities to blend our intake to the exact specification customers require, no matter what the weather throws at our members during harvest.

By Tom Allen-Stevens

As you’re swiped through the sealed door and enter the startlingly clean, air-filtered chamber beyond, it’s hard to believe you’re actually standing in a grain store. Harder still to fathom that this grain store is owned by farmers.

Technical manager Alan King has brought us to see the colour-sorter – one of the jewels in the crown of Camgrain’s Clean Wheat plant – a mesmerising machine that sifts through grain at up to 20t/hr and selects out individual items of a dubious colour as they pass over a cascade.

“We’re following a different set of guidelines,” he explains. “What passes through here meets the food-grade standards set down by the British Retail Consortium (BRC). There’s a similar chamber on every floor of this eight-storey building with processing equipment that assures our customers of the integrity of the produce they’re buying.”

The facilities are unique to Camgrain, a farmer-owned co-operative that started in 1983 and now stores 500,000t of grain and oilseeds on behalf of its 550 members. Along with its two main stores near Cambridge, there’s a 90,000t Advanced Processing Centre (APC) near Northampton, while the Stratford APC stores 50,000t for Camgrain members, specialising in rapeseed processed through the new 100,000t capacity crush that’s recently opened at the same site.

The colour sorter sifts through grain at up to 20t/hr and selects out individual items of a dubious colour as they pass over a cascade.

But it’s not just its size that makes Camgrain stand out, nor its geographic reach – it has members from the East Anglian coast to the Welsh borders, from Lincs to south of the M4. It is the only farmer-owned grain store group in the UK with a Clean Wheat plant, and this was one of the reasons it picked up the award for Supplier of the Year from Nestlé – the top accolade handed out by the food manufacturer – at its supplier event last month.

“It’s an award we’re particularly pleased to have won,” comments Camgrain marketing director Simon Ingle. “We work very closely with Nestlé to supply the exact specification they’re after for their breakfast cereal products– every box of Shreddies contains wheat produced by our members. We made the decision to invest in the Clean Wheat plant, that opened in 2008, which then meant Camgrain could compete to supply the specialist breakfast cereal market.”

It’s a contract for selected Group 4 hard varieties, as well as KWS Siskin, that returned an £8/t premium over the feed base to the Camgrain members last year by consistently meeting the required specification. “The close relationship we have with our members means Nestlé know we can meet what they require even before the crop has gone in the ground, and we can trace the provenance of the wheat in their breakfast cereals back to the individual farm. We outload the wheat to a food-graded standard and this past year have achieved a 100% score for quality and delivery to the factories we supply – another reason why the Camgrain team were awarded supplier of the year.’’

It’s at the quality end of the domestic wheat market that Camgrain sets its stall – 90-95% of what it stores on behalf of members attracts a premium of some sort. Its largest customers are flour millers in the Midlands for breadmaking wheat. “It’s consistent quality and reliability of supply they’re after,” continues Simon.

“Our Northampton APC is ideally located and we can deliver vendor-assured produce to the mill day or night. We have the facilities to blend our intake to the exact specification customers require, no matter what the weather throws at our members during harvest.”

A good example was the 2017 harvest – AHDB’s Cereal Quality survey shows just 24% of samples met the top spec for high quality bread wheat. But in the same year, 96% of Group 1 varieties sent to Camgrain achieved a premium for members.

This is one of the features Camgrain chairman John Latham appreciates most. “I can harvest at the right time to suit my crop, safe in the knowledge it will leave my farm and be stored at its optimum condition. It means I can start harvest at over 20% moisture and preserve the quality I’m looking for.”

This is one of the reasons he believes the group has grown at 10% year on year – this year there’s another 24,000t of storage being constructed at the Cambridge APC to accommodate this. “The skill of Camgrain is to take in grain of all sorts of quality and deliver out on spec,” he says.

This isn’t just down to size and logistics, though. There’s a strategic approach to marketing, managed through a close relationship with Frontier who have acted as agents for the majority of the group’s produce since 2015. And John reckons Camgrain has successfully made the transition from a group of farmers who have pooled their storage requirements, to a competitive agri-business with the experience, authority and staff to deal professionally and on an equal footing with global food businesses.

“Firstly, we have a very sound business model – we have one of the strongest balance sheets in cooperative storage with a loan to value ratio in the 30% range. Our borrowing may be higher than other farmer-owned businesses due to the scale of our facilities, but it’s invested in sector-leading assets that will be operational for a very long time, and this compares very favourably with other agri-food businesses,” he says.

“We also invest in our staff – those who work for us combine experience in the sector, with a strong understanding of members needs and, crucially, the strategic knowledge to position Camgrain as a business of the future.”

And this is where group CEO Simon Willis fits in. “My background is in the oil industry, which on the face of it may appear to be very different to the environment in which Camgrain operates, although the challenges of supply chain, personnel and financial management remain the same,” he notes.

“The biggest change for me is the ownership structure – I’m accustomed to businesses with faceless shareholders, but all the directors and farmer members play a very active role in Camgrain. The face-to-face contact is very important and you understand the long-term strategic goals shared by all the members, deeply rooted in a cultural way of farming.

“But you’re also very conscious that every penny you spend comes from the members themselves. We’re a business that is part of a lean, competitive supply chain with tight margins and there are areas that have come under scrutiny as we’ve made structural changes to ensure it’s fit for the commercial world of the future.”

That’s culminated in a review carried out by Bidwells (see panel on pxx), that John sees as part of very much how the business will position itself for future challenges. “We wanted an independent view of the benefits members get, and the areas we need to address – it’s very much a ‘warts-and-all’ review,” he says.

But as far as Brexit is concerned, there’s a quiet air of confidence among the senior management team. “99% of our target markets are domestic, while we don’t supply most of the feed markets under threat,” points out Simon Ingle. “This puts us in poll position to explore specific opportunities, such as supplying the distilling market, or displacing German E-grade wheat. It really is a tremendous opportunity that we’re looking forward to.”

The components of a compelling case

It won’t suit every farmer, but there’s a very strong case for most to consider co-operative grain storage. That’s the conclusion of a study, focused on Camgrain, carried out by David Neal-Smith of Bidwells.

“We wanted to assess whether there really was a compelling case, so looked in detail at the areas where Camgrain appears to bring value to its members’ arable enterprises.”

He looked at three areas – the capital cost, the operational costs and then whether the facilities were truly adding value to members’ grain. “In each case we compared Camgrain with what you can achieve yourself,” he notes.

On-farm costs of constructing a new store are in the order of £200-250/t, according to David, while a refurbishment of an existing storage facility can cost in the region of £100/t.

Camgrain storage costs £110/t. This is paid as a £40/t qualification loan in year one, followed by six equal annual instalments plus interest (although members can now opt for a repayment period of 10 or even 15 years). In year seven, your qualification loan is returned, averaging the capital cost to £16.50/t per year for seven years.

What’s interesting, he says is when you compare the cost for the various storage alternatives over 15 years – a reasonable repayment period for this type of investment.

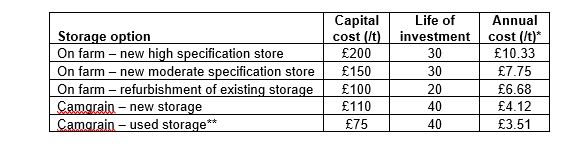

“Factoring in interest, capital repayment and tax allowances puts Camgrain storage, at £7.64/t per year, a mere 45% of the cost of a new high-specification on-farm store. Over the whole life of the storage this reduces still further to £4.12/t per year, which is 40% of the annual cost of a new store and 60% of a simple store refurbishment (see table).

“In my view, when looking at the capital cost, this shows Camgrain storage to be no-brainer, even before you’ve factored in the potential income some farmers could realise from letting out their redundant on-farm storage buildings,” says David.

“The taxation benefits are due to treating the annual instalments as trading expenses, rather than capital allowances, although this isn’t available if you buy storage from another member, which is treated as a capital investment,” he adds.

Camgrain annual operational charges are £12.95/t, which include collection and haulage to store, laboratory analysis, cleaning, storing, blending and out loading. Drying above 16% moisture costs £1.50/t per 1% removed.

“On-farm costs are harder to quantify and hence compare. Maintenance, energy, labour and management are rarely allocated as a direct charge to grain storage, so cannot easily be quantified. Then there are the hidden costs of grain deterioration and rejections,” notes David.

With Camgrain, there is the extra cost of haulage to the store, he notes, which amounts to about £6/t of the operational charges, plus the facilities and level of management and staffing you simply wouldn’t find on a farm. “These have benefits, which are hard to quantify but shouldn’t be ignored, such as those that arise from the immediate collection of grain at harvest. Simplifying the harvest operation, freeing up of labour and better timeliness for cultivations and drilling also have a value. Farmers generally underestimate all the costs associated with on-farm grain storage.’’

Finally, on adding value, David compared the annual pool returns with two commercial grain merchants, a cooperative marketing group and two cooperative stores. Over 3 years to 2015-16 Camgrain performed well across Group 1 and 2 wheat, beating the average by £3.28/t and £4.86/t respectively and clean wheat by £5.47/t. Malting barley was ahead by £6.47/t and oilseed rape by £6.30/t.

“But the pool results don’t tell the full story,” he points out. “Camgrain members successfully manage to capture the quality markets, even where grain doesn’t quite meet the top spec. The question prospective members may ask is how their grain would be treated if they marketed it themselves and sold direct off farm – would it be downgraded to feed or subject to quality claims?”

He also identifies a “third factor”. This is the cost to Camgrain members of around £6-7/t per year to enable “the Camgrain journey”, which encompasses expansion, supply chain capability and consequential repayment of debt. “This is included in the costs and reflected in the pool price return, but over time this will hopefully reduce and result in further improved pool returns,” he reasons.

So how does this stack up overall for Camgrain storage? “It’ll depend on the particular circumstances of the individual farmer,” concludes David. “But where on-farm investment is required, Camgrain offers significant benefits and should be considered carefully. For many farmers there should be a compelling case.”

The capital cost of grain storage

Source: Bidwells, 2019; *Annual cost is the capital cost shown over lifetime of asset, including interest and after tax; **Purchased from retiring member and subject to availability and price variability

Leave grain storage to the professionals

As yields increase, farms expand and the volume of grain to be managed and marketed grows, surely there’s now a case for using the expertise available of an off-farm, modern grain store offering advanced cleaning and drying equipment?

That’s the question posed by Hants grower and contractor Nick Rowsell. “The point is that grain in the field is worth nothing. Only after it has been harvested does it take on a value and that value can be affected by the timing of harvest, how it is managed in the store and how it is marketed when the time comes to sell it.”

Based at West Stoke Farm, near Winchester, Nick farms 1400ha of mainly chalk land, along with a further 290ha of less productive land 12 miles away at Crux Easton, near Newbury. Spring barley takes the lion’s share of the combinable area with 455ha being grown this year. Winter wheat (441ha) and oilseed rape (416ha) feature strongly with winter barley (120ha), winter and spring oats (144ha and 72ha) and poppies (13ha) also grown. This results in an annual production of about 11,500t of grain for which there is a storage capacity of 5800t.

“Like most other farmers involved in contract farming we had access to several grain stores and low output drying plants that had been installed several decades ago and, as such, were generally in a poor condition, or worse,” he says.

And it was this lack of quality storage which Nick says was the driver behind his decision in 2010 to purchase 500t of storage at Camgrain, a tonnage which increased during the years to the 1100t of storage he has now. He adds that having this facility also helped when he was negotiating for new contract farming business.

He reckons a modern storage and drying plant requires an investment of around £250/t and, once built, there are running costs, labour costs, devaluation costs and servicing costs.

“Camgrain asks members to make a one-off payment of £110 for each tonne of storage they need, and there is an annual handling charge of about £12.95/t, which includes transport of grain from farm into Camgrain. Drying charges, if required, generally work out to be very reasonable,” he says.

These only start on cereals above 16% moisture and Camgrain also gives credit for dry grain. “You can put the combines in and have transport available to take the moist grain to the store and put it through the driers so that the full quality and value of the grain is retained,” he points out.

Transport is a big part of the co-operative’s operation – farms with limited storage need to have regular collections during the harvest and, in Nick’s experience, there have been few problems.

Grain, he says, has been collected as and when required with each lorry load sampled and weighed when it reaches the store and the results recorded and immediately made available to the farm office.

Then there’s the ability of the store to clean, dry, and blend different grades to reach a quality level specified by a miller or brewer. “This is something that clearly can’t be achieved on-farm and an example of the way a grain store can use its expertise to achieve the best prices for its members,” he says.

So for Nick, co-operative grain stores do have plenty of benefits to offer growers. “It’s not that there isn’t still a place for on-farm storage, but having access to central storage adds an element of flexibility. Then there’s the peace of mind in knowing they can provide a safe haven for your grain – it gives you the confidence it’s stored in modern facilities, regularly monitored, and marketed at maximum value.”