It may not have turned out to be a season with big spraing problems, but free-living nematodes haven’t gone away. CPM looks at managing the threat.

The challenge for breeders is to maintain all the end-user requirements in a variety while introducing traits for resistance to pests and diseases.

By Lucy de la Pasture

As all potato growers know all too well, it’s a peculiar market where varieties are concerned. It’s not just about characteristics when it comes to which varieties to plant. There’s a huge element down to consumer and supply chain acceptance, especially for packing potatoes.

This makes it considerably different to choosing a cereal variety, where its yield and disease characteristics can make or break the decision. All too often, growers have to learn to cope with the agronomic disadvantages of a variety because it’s what the market wants.

Work at the James Hutton Institute has shown that infected seed can be an important mode of transfer for tobacco rattle virus.

To prove the point, Maris Piper is still the most popular potato variety grown in the UK, according to figures recently released by AHDB Potatoes. That’s in spite of the fact that Maris Piper is notoriously susceptible to slug damage and to Globodera pallida Pa2/3,1. Foliar blight, common scab and PVY aren’t its strong points either. Maris Piper’s success is down to its versatility for the end user, explains AHDB analyst Amber Cottingham, whose stats show the area of Maris Piper grew by 5% in 2016 (see table on below).

One of the biggest movers in the top ten was processing variety, Royal, with an area increase of 38% which moves it up six places to reach the top ten for the first time. Interestingly one of the traits of this variety is a good resistance to potato mop top virus (PMTV) which causes spraing symptoms in tubers. Another top mover is Taurus which has a resistance (8) to powdery scab, which acts as the vector for PMTV. Could that be a coincidence or a reflection that growers do what they can within their market when it comes to variety selection?

“The main problem at present with varieties is getting them accepted by the end user. They may be resistant to everything but if they don’t taste, cook and process right then they’ve no chance,” explains independent potato specialist, John Sarup.

One of the key things growers aim to do to counter agronomic weaknesses in the varieties they’re growing is to match them with fields. This is particularly important when it comes to spraing control, believes John Sarup but he reckons that PMTV isn’t the biggest cause of spraing symptoms.

While fields that harbour powdery scab are often well known to growers and managed accordingly, the second and most important virus causing spraing symptoms, tobacco rattle virus (TRV), is transmitted by a group of tiny soil inhabitants, the free-living soil nematodes, which are less well understood, he explains.

Potato plants become infected with TRV from nematodes in the soil that feed on the developing tubers, explains Dr Roy Neilson, nematologist at the James Hutton Institute.

“Not every species of free-living nematode can carry TRV. Transmission is by free-living nematodes of the genera Trichodorus sp. and Paratrichodorus sp. (stubby root nematodes) and tends to be a greater issue on light, sandy soils,” he says.

So far this season, John Sarup has seen very few spraing issues, especially surprising after the lack of Vydate (oxamyl) in the spring which is normally applied in an effort to control free-living nematodes. So why does he think this is?

“One of the main factors is probably the added focus we had on matching the right variety to the right field because we needed to manage the crop without Vydate being available. Now we’ve gone through this targeting process, it’s something we should continue to do as a matter of good agronomic practice and consider the use of Vydate as an additional insurance measure,” he says.

“Another big factor was probably the weather. It was dry during tuber initiation which means the nematodes wouldn’t have been able to move around and transmit the virus at this important time,” he suggests.

Nematodes favour wet conditions because they can only move around in soil water, so heavy rainfall or over irrigation can also exacerbate incidence of spraing in some seasons.

One of the big factors when it comes to field selection for spraing-prone varieties is weed control. Host weeds for TRV can be a major factor and eliminating the green bridge is something to be mindful of, advises John Sarup.

“TRV virus has been shown to have a very broad host range and can infect over 400 plant species. These include many common field weeds including fat hen, chickweed, knotweed, bindweed, groundsel and dandelion,” he explains, adding that some of these weeds are common in grassland so virgin potato ground can’t be assumed to be free from virus vectors where TRV is concerned.

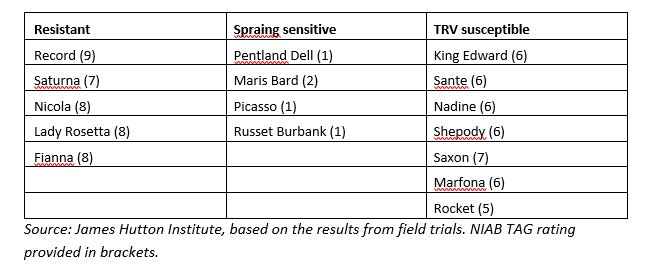

It’s currently thought that there are three types of response to TRV by different potato cultivars. Some cultivars, such as Record, are immune to TRV infection, although isolates of TRV have arisen that can overcome this resistance, explains Roy Neilson.

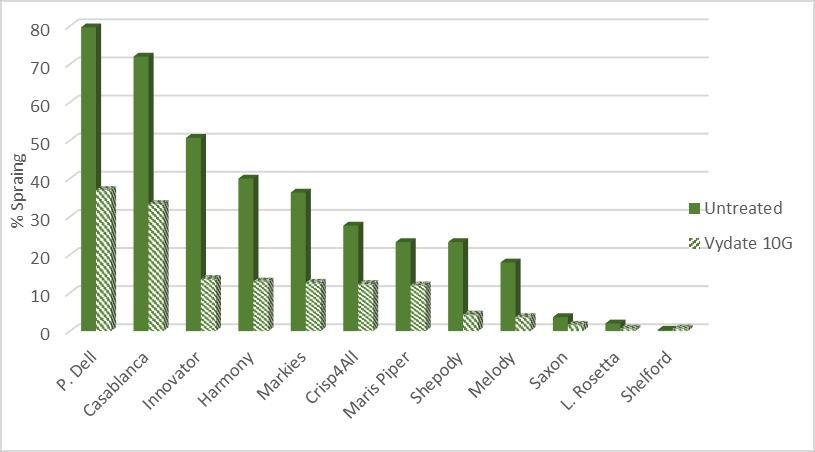

Potato varieties exhibiting spraing symptoms

Source: AHDB; results from a site in Shrops (2012); presence of TRV confirmed using diagnostic tests performed by SASA.

A second group of cultivars, which includes King Edward, Sante, Nadine, Shepody, Saxon, Marfona and Rocket, are completely susceptible to TRV.

“This means that the virus spreads throughout the infected plant causing little or no observable symptoms but the plant is systemically infected. Work at the James Hutton Institute has shown that infected seed can be an important mode of transfer for the virus and after several generations such potato plants produce smaller and more irregular tubers.”

The third group of cultivars, which includes Pentland Dell, react to TRV infection by producing arcs of discolouration (spraing symptoms) inside the tubers, as well as surface lesions and malformations.

Testing for free-living nematodes has traditionally been carried out under the microscope but this season, growers have an additional molecular option developed at the James Hutton Institute, with the collaboration of a number of industry partners, and launched in Aug at Potatoes in Practice.

“Until now, when growers submit a soil sample, they get a result that indicates the number of stubby root nematodes detected in the sample. The problem is that a number of stubby root species coexist with the two species of free-living nematodes that are TRV vectors. Under the microscope it’s not possible to distinguish how many are virus vectors and how many aren’t,” explains Roy Neilson.

Funded by AHDB Potatoes and Innovate UK, he describes the new molecular DNA diagnostic test as a real step forward.

“The new test will differentiate between the different species of FLN so gives growers more pertinent information. It’s quicker and potentially cheaper because the throughput of samples that can be analysed in a day is much higher than performing taxonomy using a microscope,” explains Roy Neilson.

The diagnostics has undergone three years of validation and been tested against approximately 5000 soil samples from potato-growing areas of the UK. In parallel, this has enabled scientists at James Hutton Institute to potentially identify molecular markers which will facilitate future breeding of new potato varieties with resistance to TRV and to develop strategies for controlling free-living nematode.

“Free-living nematodes have always been endemic in UK soils but the focus has always been on potato cyst nematodes (PCN). There’s been a sharper focus on free-living nematodes over the past few years with the realisation that the chemical control options available are likely to decrease dramatically,” he adds.

This realisation has been further sharpened by forecasts that the numbers of free-living nematode species are likely to continue to increase as the effect of climate change influence the dynamics of our soil fauna and flora.

Sue Cowgill, crop protection scientist at AHDB Potatoes, explains that the molecular diagnostics is just one component of a much larger five-year research programme to address the free-living nematode problem and is the first to reach completion.

“A second component of the project is looking at the broader community of free-living nematodes that attack potato roots and cause losses in yield and quality. The current information we have regarding nematode thresholds for damage and when a nematicide treatment should be considered is old, so this is in the process of being updated,” she explains. “We’re looking to see how plants respond to free-living nematodes in field trials at four sites, from Norfolk to Scotland, with 12 cultivars at each location.

“We’ve observed that conditions which affect the speed of plant emergence and early growth can affect the severity of nematode damage, but in an average year, damage isn’t as substantial as we originally thought. But there will be situations where there’ll be a benefit from using a nematicide,” she says, adding that a risk assessment will ultimately be produced so that growers can better identify the risk on a field-by-field basis.

John Sarup believes that looking at the effects of the free-living nematodes beyond the transmission of spraing is important research. “It’s the whole umbrella of free-living nematodes we need to understand more about. There are issues around direct feeding damage to the roots, which also creates a point of entry for pathogens. Of particular concern is the ‘early dying complex’, which consists of a number of pathogens including verticillium and rhizoctonia,” he says.

The third component of the AHDB research is looking at the variety responses to TRV infection to identify markers to use in breeding programmes. “It’s impossible to be prescriptive where free-living nematodes are concerned and each field needs to be assessed on the basis of its history, soil type and condition and whether TRV is present.

“The solution will be a very integrated approach and there’s a lot more to come in the future from cultivars, which will aid spraing control in particular,” she believes. “The challenge for breeders is to maintain all the end-user requirements in a variety while introducing traits for resistance to pests and diseases.”

In the meantime, autumn is a good time for taking soil samples to test for free-living nematodes, advises Roy Neilson.

“Autumn and spring are the best times of year for getting representative samples from the field, when temperatures aren’t baking and there’s enough moisture in the ground. If growers can get samples in as soon as possible it helps with field selection for next year’s potato varieties,” he adds.

On a cautionary note, John Sarup suggests growers send any potatoes with internal browning for testing to make sure it’s spraing they’re dealing with. “Internal rust spot and spraing can easily be misdiagnosed and while the marketing implications are the same, it’s important to establish whether the cause is related to a calcium problem or is a symptom of a viral infection,” he says.

“If you have spraing, it means that you have free-living nematodes that are carrying TRV. The implication is that weed control needs to be a priority throughout the rest of the rotation, otherwise the virus will still be there when the field comes back into potatoes again,” advises John Sarup.

Spraing sensitivity